The supposed leak did not have any sample data for verification, according to cybersecurity experts

The health ministry has also denied the breach of Covid vaccination data of 150 Mn Indians

The CoWIN app does not have a privacy policy, according to a government response to an RTI inquiry

The rising interest around cryptos globally and Covid vaccination collided this week in India in a peculiar scam that misled Indian citizens into believing that their CoWIN user data had been stolen and was being sold on the dark web. But while initially, it raised a scare among Indians, the supposed leak turned out to be nothing but an attempt to grab Bitcoins from the Indian market, according to cybersecurity experts.

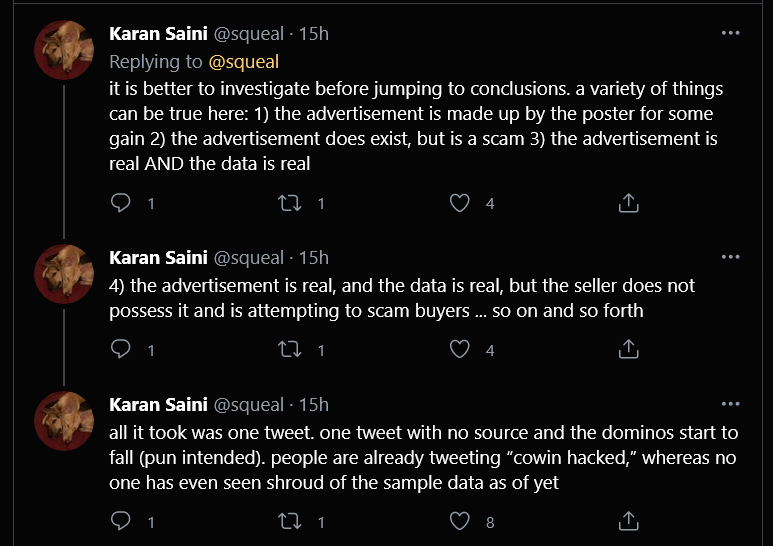

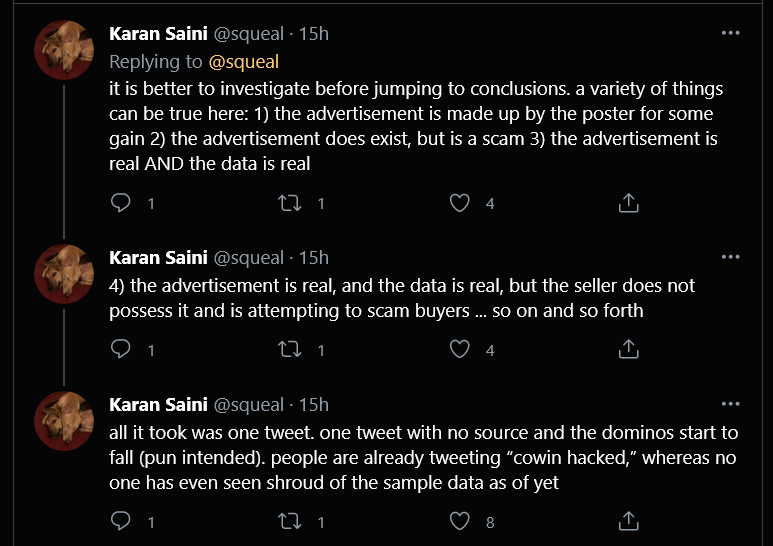

As spotted by security researcher Rajsekhar Rajaharia and others, the supposed data leak was not real. Besides this, the health ministry has also denied the breach of Covid vaccination data of 150 Mn Indians, after news of the hack spread on social media and news websites, without confirmation and no proof of the data actually being authentic, as pointed out by security researcher Karan Saini. This created a lot of unwarranted panic on the internet and on social media.

Rajaharia said the particular dark web market which is claiming to sell the information has a history of posting fake data leaks and scamming unsuspecting people who may want to protect their information. “They are just taking Bitcoin for nothing. Data sample also not available anywhere,” he said.

He added that just for viewing sample data, the supposed hackers are charging $180 in Bitcoin, which is something legitimate data leaks never do.

RS Sharma, head of the CoWIN platform, said in a statement, “Co-WIN stores all the vaccination data in a safe and secure digital environment. No Co-WIN data is shared with any entity outside the Co-WIN environment. The data being claimed as having been leaked such as geo-location of beneficiaries, is not even collected at Co-WIN. The news prima facie appears to be fake. However, we have asked the Computer Emergency Response Team of MeitY to investigate the issue.”

Of course, while this particular instance may not have been about an actual data leak, there is a lot of ambiguity around the privacy policy of CoWIN and the Aarogya Setu app, which is also used for vaccine registration.

The CoWIN app, for example, does not have a privacy policy, according to a government response in April this year to a Right to Information (RTI) inquiry by the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF). The government contended that the app was not for public use but only for registration for the vaccination and therefore the real users would be national, state and district-level administrators. Presumably, these entities do not need a privacy policy.

This despite the CoWIN app actually collecting data such as names of the registrants, their gender, date of birth (DOB), photo ID, type of photo ID and mobile number. The IFF also didn’t receive a clear response to its query about which ministries and departments in the government will have access to the data on the CoWIN platform.

Government Apps Fail Privacy Test

The Indian government’s propensity for using technology for governance has led to mobile applications that have eased the delivery of public goods and services. However, with India yet to notify a personal data protection legislation, many of these apps developed by the government are found to have security vulnerabilities that clearly jeopardise user privacy. The Aarogya Setu contact tracing app for example did not have a clear mechanism to track what data is being shared and with whom.

In April, the Delhi High Court granted bail to activist Umar Khalid seven months after his arrest under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (aka UAPA) of 1967 for his alleged involvement in the Delhi riots of 2020. While the charges under UAPA are still pending, the court decided to let Khalid out on bail against the payment of the INR 20,000 bond and a surety of like amount.

While all that was part of due legal procedure, there was one condition that raised a lot of eyebrows — Khalid was asked to install the Indian government’s Covid-19 contact tracing app Aarogya Setu on his mobile phone.

However, while defending the app against privacy concerns, the government had stated that the app cannot be used to track individuals. So the court’s order raised questions about whether the government was being truthful about the potential for Aarogya Setu to be used as a surveillance tool.