The Indian government’s enthusiasm for e-mobility is admirable, but the timing on some of the policies it has created is off, according to Chetan Maini, Co-founder and Chairman, .

Drawing attention to the fact that there are 50-plus EV players in the country, some thousands of EV parts manufacturers—and more coming up each day—Maini believes the sector has become an entirely different beast, one that needs a different approach to the one regulators have taken up until now.

“You know… regulators are truly trying to do as much as they can. But it’s hard for the government also because there are all these technologies coming from different centres, and they don’t have a perspective of each thing,” he tells YourStory in an interview.

The government’s attitude towards the EV space today is radically different than what it was back in the 1990’s when Reva—a pioneering electric vehicle designed and engineered by Maini—was launched.

Reva flagged off the e-mobility movement in a lot of ways by becoming the first electric vehicle to invade public consciousness in the country. More importantly, it signalled that a good Indian electric vehicle could be produced in India, and there was no need to look toward the West.

“When you go to the government today, they’re actually saying that we need electrification of vehicles to happen. They’re constantly asking the industry ‘what can we do’?”

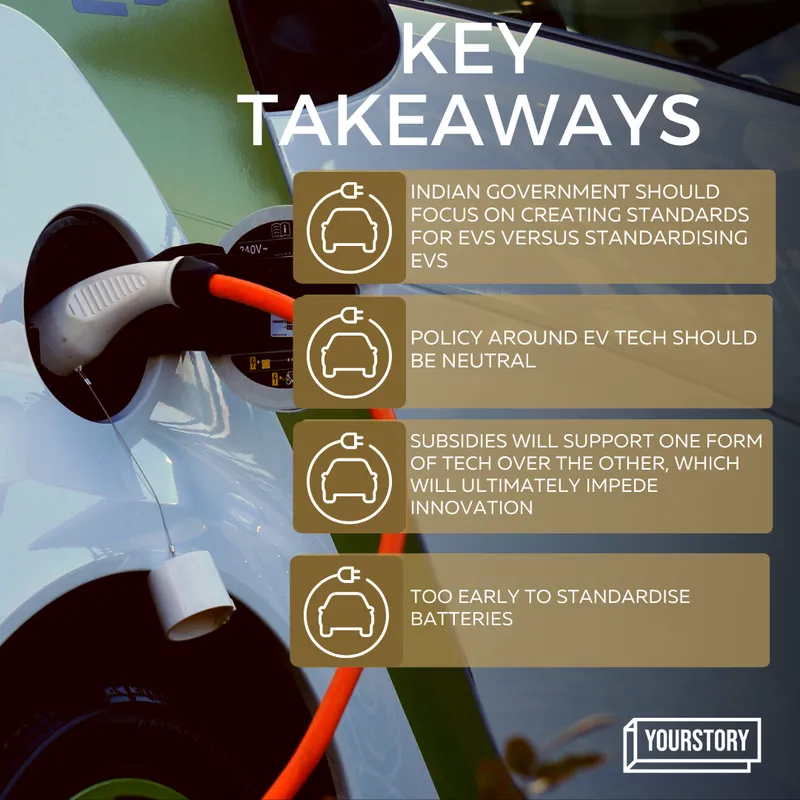

Regardless, Maini says he’s opposed to several policy moves made by the government in the past year. For one, he’s dead set against the standardisation of batteries and battery packs at this point in time.

Too early

Standardisation of EV batteries will essentially impede any innovation, which is vital right now from the perspective of safety and its overall adaption to Indian temperatures and road conditions—the entirety of which require specific solutions, Maini says.

Instead of force-fitting a particular battery model or set of specifications, the right way to go about standardisation would be to let market forces decide, and then bring in regulations once the market has consolidated around a few dominant, widely available options.

“To say ‘hey, everything should be exactly this particular size’ when technology’s changing every year, will constrain innovation. In the early years of a new technology, different things should coexist; and then as the tech matures, you could start to standardise,” he says.

“Allow the industry to build in multiple solutions, and, at the point of high growth, bring regulation in. But in the early days, which we’re in right now, standardisation will only hurt more than help.”

Of course, you could fault Maini’s philosophy for looking out for number one, considering Sun Mobility also manufactures its own battery packs, and has set up swapping stations only to service its batteries.

But even non-battery manufacturers in the space—including leading OEMs—have said they don’t want standardisation because they may want the ability to customise the battery technology used in their EVs to differentiate their products from those of their competitors and to meet the specific needs of their customers. Standardisation could limit this ability.

More importantly, some OEMs may not want to commit to a specific battery technology if they believe that a superior alternative may become available in the near future. Standardisation could lock them into a particular technology for an extended period of time.

Don’t tie tech to subsidies

The National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP), although formulated with good intentions, was ultimately unsuccessful due to the government’s inability to effectively implement it.

This, coupled with the demotivating effect of the prior removal of incentives, exacerbated the challenges faced by the industry. Ultimately, all of this hindered the growth and development of the electric vehicle industry in India, causing a delay of several years before it began to recover.

But what about incentives, especially subsidies, today? What about the deep tax breaks companies get for operating in the EV sector, manufacturing vehicles, etc?

Maini argues that subsidies may not be the most effective solution in the current situation, and could even have unintended negative effects. He believes that any policy around EV technology should be neutral, and not incentivise one over the other.

“If a customer walks in to buy an electric vehicle with or without a battery, the benefit they get should be the same; only the model and its features should matter,” he says, adding the playing field should be level.

To be sure, Maini does not oppose subsidies—he merely wants everyone in the ecosystem to either not receive any subsidies at all, or be given the same benefits, so that when a customer walks into a showroom, they’re not subliminally coerced into picking the cheapest option (which could be cheaper only because of the subsidies given to the manufacturer.)

In fact, he opines that homogenisation of swappable batteries and then tacking on a subsidy on them would be misguided because it would indirectly incentivise manufacturers to prioritise obtaining the subsidy over consistently striving for superior battery pack performance.

“Today, we don’t say your fixed battery has to be XYZ size and only then you’ll get a subsidy. So, there’s no reason to do that on swappable batteries either.”

So, if subsidies are not the solution, and standardisation is not currently feasible, what should the government focus on instead? Which legislative priorities would be most effective in guiding the development and growth of the emerging electric vehicle industry in India?

Standards, not standardisation

Maini believes the Indian government should prioritise creating standards around the safety of electric vehicles, implementing those safety standards, and ultimately understanding the customer better.

“Five-10 years ago, we didn’t understand things like five-star ratings on air conditioners, or tyres, but the government created those safety standards and made sure people understood them. If a customer walked in and said, “I want to get a swap from company A or B”, how would they know which one is better, or more efficient?”

“It’s important to help create standards around how consumers understand a new technology better,” says Maini.

Standards around safety that are galvanised in the law will also clue in battery manufacturers and OEMs into the direction the government could take when it homogenises batteries, which would, hopefully, be sometime in the future, he says.

In light of the EV fire accidents earlier this year, the government of India created guidelines around battery safety and some other components of an EV, such as battery management systems, battery cells, and onboard chargers, among other things. The draft notification requires that traction batteries used in electric powertrain vehicles meet the standards for conformity of production.

Minister for Road Transport and Highways, Nitin Gadkari, has warned companies that if they were found responsible for any adverse EV events, they could be ordered to recall defective vehicles.

India should set the standards

Even if things didn’t pan out for Reva in India, its very existence set into motion a broader, consumer-focused discourse on electric mobility in the country, even just among the general public.

India, the world’s largest market for two-wheelers, has the potential to become the global standard in safety, standardisation, and legislation around EVs, Maini says, echoing Bhavish Aggarwal, who said something similar along those lines at YourStory’s TechSparks 2022 event.

“If the industry were to align with government standards, we could have a multiplying effect in the larger world. We need to create standards that we can take across the world—that should be the philosophy we use when we create EV legislation, and I think the government’s intention is that, but the drafts we’ve seen so far don’t represent that.”

“We need to take a step back and see what’s right for the country—not any one company or player.”

![Read more about the article [Funding alert] EV startup Euler Motors raises an additional $2.6M in Series A round](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Euler1571068358401jpg-300x150.jpeg)