During the pandemic, as India’s edtech sector grew at a rapid pace, there was a frantic rush to close acquisitions. Market leaders like , and were closing large, nine-digit takeovers, in step with the heated funding activity.

However, with online learning giving way to hybrid education and throwing the edtech sector in turbulence, M&A activity has also cooled down, with the number of deals declining by a third to 15 in FY23 from 45 in the previous fiscal year.

While large firms tighten their purse strings amid the funding winter, mid-stage companies continue to acquire. Industry experts believe that the edtech space is now heading towards a measured phase of M&As.

“This time, the consolidation will not happen in a hurry, and it will not happen in one burst as it happened post-pandemic,” Narayanan Ramaswamy, National Leader of Education and Skill Development at KPMG in India, tells YourStory.

Edtech firms—both billion-dollar valuation companies and especially the smaller ones—will take more calculated bets going forward, even though they may be flush with capital, as the market conditions continue to be unfavourable.

From mega to mini deals

BYJU’S led the edtech acquisition spree when it purchased WhiteHat Jr for $300 million in August 2020. Then, in January 2021, it acquired Aakash Educational Services for a mammoth $1 billion, closing the world’s largest edtech acquisition by a venture capital (VC)-backed company. A few months later, it purchased Great Learning for $600 million and Toppr for $150 million.

A Moneycontrol report also noted that Unacademy and Aakash are considering a possible merger. However, BYJU’S and Aakash have denied any such development.

The edtech giant was among the top acquirers in the past two years, along with other unicorns like Unacademy and upGrad, according to Tracxn. Interestingly, their consolidation efforts were driven by large funding raised from domestic and international investors.

The fall in the number of acquisitions follows a sharp drop in edtech funding—which has plummeted to $1.33 billion raised in April 2022 to March 2023 from $6.22 billion in the comparable period a year prior, as per Tracxn.

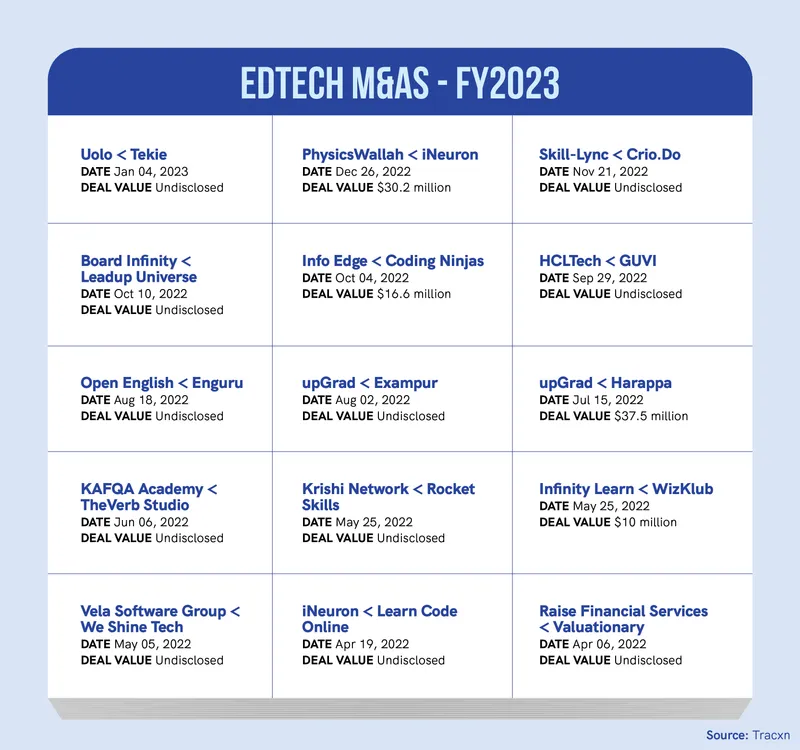

The size of the edtech M&As has also shrunk. According to the data platform, the average size of 10 (disclosed) out of 45 deals between April 2021 and March 2022 was $112 million, while the average size of 4 (disclosed) out of 15 deals a year later was $23.5 million.

This shift is represented by the recent acquisition of upskilling platform iNeuron by edtech unicorn PhysicsWallah (PW) for $30.2 million.

Infographic credit: Nihar Apte

Who’s buying?

BYJU’S, one of India’s most valuable startup, has spent over $3.48 billion on 21 acquisitions and two investments, as per Tracxn. It has invested in multiple sectors such as K-12 (kindergarten to 12th grade), continued learning, test preparation tech, and more.

But the edtech decacorn has been plagued with mounting losses, layoffs, and pending loans. The company has also come under scrutiny for its accounting practices.

An investor at an early-stage venture capital (VC) fund tells YourStory anonymously that BYJU’S will not be buying companies, at least for the next one or two years. The company has also set a bad precedent—acquiring aggressively can come with the same challenges the edtech unicorn is going through, he added.

Besides, currently, not many buyers can execute acquisitions, he remarked. “We have firms that might want to sell, but we do not have a lot of companies that can potentially buy.”

“Larger companies, which had deep pockets a year ago, are cutting costs left, right, and centre. It is very unlikely that they will just go out and buy some (smaller) firms because most acquisitions have turned out to be lemons,” says Siddharth Shah, who is a part of the investment team at Malpani Ventures.

Which begs the question: who has the firepower to pay?

The first investor noted that unicorns like PW, upGrad and Eruditus can take bets “only if it makes sense for their core business and they will not go around experimenting, which is something BYJU’S has tried quite a bit.”

PW, a rare profit-making edtech startup, has been on a buying spree ever since it became a unicorn after raising $100 million in June last year from WestBridge Capital and GSV Ventures.

“We have already spent $40 million for M&As and we have $60 million more committed towards this purpose,” Prateek Maheshwari, Co-founder of PW, tells YourStory. Some of the acquisitions, including PrepOnline and Altis Vortex, were targeted at strengthening PW’s NEET, GATE, and similar test prep categories. Other deals were directed at expansions.

In March, PW acquired UAE-based startup Knowledge Planet, marking its first international acquisition. PW is also planning on expanding to Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, as well as to parts of North Africa.

On the build versus buy debate, Maheswari says PW prefers to build first. “We only buy with a specific reason; either they have solved a deep pedagogy, which will take a lot of time to solve, or they have created a unique distribution,” he notes.

Maheswari explains, “If you spend the same time, effort and sweat, as well as money you are going to spend in terms of creating the same thing, then buying things makes more sense.”

For PW, which is going through a “hyper-growth” phase, buying, perhaps, makes more sense as it helps the company maintain the growth momentum.

Different approaches to deals

Acquisitions help companies increase their user base, add more offerings to their portfolio, diversify geographically, eliminate potential competition, or obtain technology and expertise.

Ramaswamy of KPMG expects more consolidation in the edtech sector, however, companies may shun volume and look at specific areas where they can bring value, he adds.

According to him, there can be two kinds of acquisitions—the first would involve larger players that can raise funds or have surplus money, and want to spend on increasing capacity.

In March, upGrad, which has made 16 acquisitions, according to Traxcn, raised Rs 300 crore in internal rights issues from existing shareholders and founders. The company will focus on organic and inorganic growth across multiple verticals of formal education.

In the same month, another edtech unicorn, LEAD, acquired London-headquartered learning firm Pearson’s local K-12 learning business in India. Its deal was closed a couple of months after LEAD raised about $20 million in debt.

The other kind of acquisition involves small players coming together to compete with larger players. “As the ecosystem gets clearer, smaller players that do not have access to finances but are working in complementary space will come together,” Ramaswamy notes.

Last month, K-12-focused Toprankers, armed with $4.67 million it raised over two funding rounds, acquired career guidance platform ProBano in a cash-and-stock deal. Like many other edtech firms, Toprankers, which focuses beyond engineering and medicine entrance exams, is also looking to expand in the offline space.

“Rather than starting from zero, we will just acquire an institute and rebrand it as Toprankers,” says Gaurav Goel, Co-founder and CEO of Toprankers, adding that the firm is sufficiently capitalised.

Infographic credit: Nihar Apte

Cash isn’t king

With edtech companies trying to burn as little cash as possible amid the funding crunch, most of these deals are likely to be a mix of cash and stock. According to Ramaswamy of KPMG, all small acquisitions will be on a cash basis, while any large acquisition will have a significant swap of equity.

Experts say many companies prefer stock-heavy deals as it allows them to use their inflated equity.

“A smart seller would not be very happy. But if there is a desperate case, a firm would rather find a buyer and take that overvalued equity, considering it is quite difficult to shut down a company,” remarks the anonymous early-stage investor.

However, the value of equity can change over time.

“Unfortunately, the problem right now is that the other founder (seller) also understands the value of equity,” Goel of Toprankers says, explaining that while the buyer would be keen to give equity, the seller prefers upfront cash.

Survival of the fittest

Does the slowdown in M&A activity threaten the survival of small, cash-strapped edtech companies?

“Many smaller companies either have shut shop or they have already been merged with other edtech companies. Some of them have become profitable so they can operate with positive cash flows,” the anonymous investor notes.

In April, Bengaluru-based DUX Education stopped operations after struggling to raise funds.

Shah of Malpani Ventures, which backed DUX Education, notes that most of the capital raised in the last two years did not fund early-stage companies, which has left them with little gunpowder. In the past year, the majority of the funding in the sector (~45%) was raised by top unicorns, according to Tracxn.

The majority of edtech companies acquired are early-stage, the private data firm noted, as established players look to take over struggling businesses.

Firms that are not able to scale beyond a certain point would either get acquired or merge with other entities, while some would lean toward joint venture-like arrangements, according to industry experts.

“Consolidation is most likely to happen, and in consolidation, either some companies will die or they will be acquired for bits and pieces, or maybe just the team members. But it is a reality. It is happening and some sort of clear out is possible in the next year or so,” Shah notes.

With investors cautious about edtech companies, many smaller players would go for M&A, according to Goel. “Maybe 12 months from now, either a lot of edtech companies will consolidate or die.”

(Cover image and infographics by Nihar Apte)