Launched in 2012, YourStory’s Book Review section features over 350 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

Tips and examples for individual and organisational creativity are well-described in the engaging book, Lateral Thinking for Every Day: Extraordinary Solutions to Ordinary Problems by Paul Sloan.

Drawing on the work of Edward de Bono’s 1967 book The Use of Lateral Thinking, the author describes lateral thinking as a problem-solving approach using indirect and creative standpoints. It helps innovation for tackling a range of individual, organisational and social problems.

Paul Sloane is the author of How to Be a Brilliant Thinker and The Innovative Leader, and editor of A Guide to Open Innovation and Crowdsourcing. He was earlier at IBM, Ashton-Tate, MathSoft, and Monactive. See my review of his earlier book, The Leader’s Guide to Lateral Thinking Skills, and author interview.

“Lateral thinking will help you to become a much more effective problem solver, a more creative innovator and a more interesting person. It will enable you to generate many fresh, better ideas,” Paul begins. His new book offers a wealth of tips and examples across industries and beyond the usual suspects.

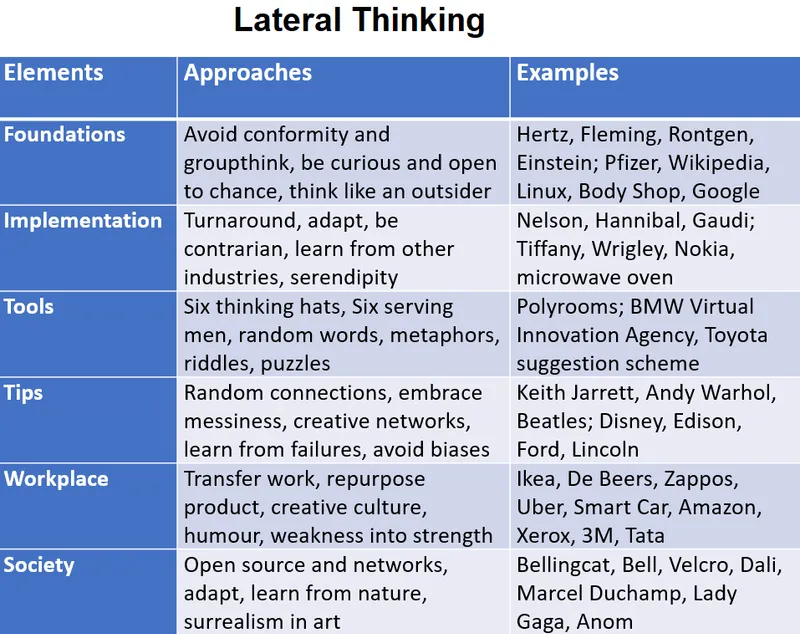

Here are my key takeaways from this enjoyable and practical 225-page book, summarised as well in the table below. See also my reviews of the related books: Mix and Match, Social Chemistry, The Art of Noticing, Non-Obvious Trends, The Serendipity Mindset, Experiencing Design, and The Creative Thinking Handbook.

I. Foundations

As described by De Bono, lateral thinking involves the recognition and deviation from dominant polarising ideas, and the use of chance. It is powered by questions like What if?

“You will start with silly ideas but these often lead to radical insights and innovations,” Paul affirms. Examples include low-cost airlines that broke rules of the traditional aviation industry.

Paul cautions against the dangers of conformity, group think, and dwelling in echo chambers. “Because we are all prey to the forces of group conformity, we need lateral thinking,” he affirms.

It is important to be open to dissent and controversial viewpoints. Outside perspectives and whistleblowers should be welcomed to create vigilance and question assumptions. Otherwise, this can lead to a fall from grace, as seen in the case of collapse of Enron, bankruptcy of Swissair, and Volkswagen emissions scandal.

The business world has witnessed steady disruption in waves of expensive, cheaper and free products, eg. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Microsoft Encarta, Wikipedia. Other examples are Uber, Airbnb, Linux, and the Body Shop.

Lateral thinkers are rulebreakers, as seen in Don Estridge’s open architecture for the IBM PC, Muhammad Yunus and microfinance, and even Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody. Immigrants can also be lateral thinkers due to their outsider mindset, eg. Levi Strauss, Elon Musk, Sergey Brin. Many fast-growing startups are founded by immigrants.

Lateral thinkers are curious and ask questions others may even perceive as dumb. “Lateral thinkers never stop asking questions because they know that this is the best way to gain deeper insights,” Paul affirms.

“Some people are afraid that by asking questions they will look weak, ignorant or unsure,” he says. However, asking questions is a sign of strength, not weakness.

Paul cites a number of innovative companies who have made a complete turnaround. Examples include Tiffany (from stationery to jewellery), Berkshire Hathaway (from textiles to financial services), Avon (books to cosmetics), Nintendo (playing cards to video consoles), Wrigley (baking powder to chewing gum), Hasbro (textiles to toys), and Nokia (boots, mobiles, networks).

Paul cautions against the complacence and even arrogance that being knowledgeable may bring. Innovators who faced considerable resistance from established experts include Ignaz Semmelweis (antiseptic cleansing), Alfred Wegener (continental drift theory), and Per-Ingvar Brånemark (dental implants).

“It is a curious fact that the best educated people are often the ones most resistant to fresh ideas,” he laments. A lateral thinker is not a ‘zebra’ (Zero Evidence But Really Adamant).

“Design your experiments so that you can fail safely,” Paul writes. Fast feedback loops and risk management were exhibited by Paul MacCready, creator of the Gossamer Condor and Solar Challenger.

Lateral thinkers also create conditions where they can benefit from serendipity, and are open to unusual creative behaviours of customers.

Examples include Thomas Sullivan (teabag), Percy Spencer (microwave oven), and Scott Burnham (Rat guitar pedal). Being open to chance has been leveraged in a range of inventions by Hertz, Fleming, Rontgen, and Pfizer (Viagra).

“Lateral thinkers are open-minded and quick to learn from accidents. They are ready to observe and adapt when the unexpected happens,” Paul emphasises.

II. Tools and tips

The author shows a wide range of lateral thinking techniques in action, such as Six thinking hats and the Disney Method.

Other recommended methods are The Three Greeks (ethos, pathos, logos, or authority, emotions, logic), SCAMPER, 51 miles (similes), and The Six Serving Men (positive and negative perspectives along with six questions: what, why, when, how, where, who).

The Random Word method forces connections between a word or its attributes and the problem to be solved. Paul recommends the use of simple concrete nouns rather than abstract nouns. Random pictures, objects, songs, and rolls of the dice can also be used.

“To be really creative, you need to generate a large number of ideas before you refine the process down to a few to test out,” Paul writes. Examples of crowdsourcing for ideas include BMW’s Virtual Innovation Agency and Toyota’s in-house suggestion scheme.

Other creative tips offered in the book are reading random kinds of articles and publications, connecting with outsiders, travel to unusual places, signing up for courses in unconnected disciplines, and having random lunches. “Visit museums, art galleries and libraries,” Paul adds.

Lateral thinking also involves embracing messiness and unpredictable situations. Examples include jazz pianist Keith Jarrett, who famously improvised during a concert when he had to play on a faulty piano.

“If you want creative ideas then mix with creative people,” Paul advises, while also making the case for individual self-reflection. “Some creative geniuses work alone but many work in tandem,” he adds.

Bouncing back from setbacks and failure is also key for creative success. “Experiencing failure can be a learning experience and an opportunity for a fresh start,” Paul affirms.

He lists five reflective questions to ask during setbacks: What can I learn from this? What could I have done differently? Do I need to acquire or improve some skills? Who can I learn from? What will I do next?

“Use your setbacks as learning experiences and make them stepping stones to future success,” Paul advises.

He also cautions against a range of biases that come in the way of creativity: affinity bias, anchoring bias (relying on the first piece of information), authority bias, availability bias, confirmation bias, gambler’s fallacy (‘bad luck will be followed by good luck’), and social proof.

III. Organisational creativity

One section of the book profiles lateral thinking principles in action in the business sector. Examples include transferring some work to the customer to give them a sense of achievement, eg. Ernest Dichter (requiring customers to add eggs to cake mix), Ikea (furniture assembly by customers).

Companies who successfully repurposed their products and changed track include De Beers (from industrial diamonds to engagement rings).

Zappos, headed by the late Tony Hsieh, had a culture where employees could self-organise and update the company’s culture book. The company now consults other firms on how to improve their cultures, and offers leadership training courses (‘School of Wow’).

Companies implementing lateral thinking focus more on the current problem than on existing players, as seen by the rise of Uber and Airbnb. “Every problem is an opportunity for innovation,” Paul advises.

A sense of humour and even mischief can help in designing marketing campaigns that stick out, though they may seem controversial to some. “If you have an important message to convey, assess the risks, consider using humour or provocation,” Paul advises. Examples include Burger King’s ads for a ‘left-handed hamburger.’

Innovators who have successfully adapted ideas from other industries and countries include Henry Ford (car assembly line based on meat packing factory), Ray Kroc (car assembly model adapted to restaurants), Clarence Birdseye (frozen foods), and Jorn Utzon (Sydney Opera House design based on boat sails).

Paul shows how inspiration for combinatorial ideas can come from hybrid cafes (Manuscript Writing Café in Tokyo; cat cafe Meow Parlour in New York) or innovative restaurants (Macaroni Grill’s free food on Monday or Tuesday, all-glass undersea restaurant Ithaa in the Maldives, Amsterdam’s Kinderkookcafe with children as staff).

Housing block PolyRooms are designed to be stacked like Lego bricks, while Lego itself conceived of a corporate training strategy using its bricks as creativity tools. In addition to borrowing ideas, companies across sectors can collaborate as well. For example, Mercedes-Benz and Swatch collaborated to create the Smart Car.

Suggestions and ideas should be embraced with a ‘Yes and …’ rather than ‘Yes but …’ approach. Amazon has strengthened idea implementation with ‘The Institutional Yes.’ Employee suggestions that are turned down have to be explained by managers with a report justifying the refusal. “Amazon has made it much easier to say Yes rather than No,” Paul shows.

Innovative companies have a strong culture of experimentation and adapting products that may not have been deemed successful initially. Examples include the Post-It.

“Change your attitude to risk; don’t minimise risk, manage it,” Paul advises. “If you want an agile, creative and innovative business, then the motto is experiment, experiment, experiment,” he adds.

“Failure is an essential part of the exploration and trial of new ideas, whereas success can breed complacency, self-satisfaction and aversion to risk,” he cautions.

“Caution can be an enemy of success,” Paul observes. “If you cut out the possibility of failure then you limit your chances of success.”

He cites Mike Malone’s distinction between two types of failure: honourable failure (genuine attempt) and incompetent failure (faults in individual performance). “Recognise and reward heroic failures,” Paul advises.

For example, the Tata group has a Dare to Try award category which comprises “courageous attempts that did not achieve the desired results but have potential for success.”

IV. Lateral thinking in society

Going beyond many creativity books, Paul also highlights lateral thinking in social, political and cultural contexts.

For example, Henry Charles Keith Petty-Fitzmaurice’s views on how to deal with Germany after World War I and Konrad Kellen’s analysis that the Vietnam war was not winnable were met with outrage and even hostility.

“It takes great courage to challenge the powerful and the popular. We need that courage time and again,” Paul reminds us.

Joseph Stalin and Robert Mugabe stuck to their wrong precepts, while Mikhail Gorbachev and FW de Klerk changed their ways, the author explains.

English journalist and blogger Eliot Higgins founded BellingCat as a journalistic group which would investigate war crimes and major incidents using open-source intelligence.

“Knowledge can breed certainty, hubris, and closed minds. We need to be open-minded and even doubtful about our knowledge because what was true yesterday may no longer be true today,” Paul cautions.

“One of the best sources of fresh ideas is the natural world,” Paul observes. As examples, he cites female cuckoos (using nests of other birds), porcupine fish (pufferfish), wood frog (self-freezing technique), and termites (mound design). Nature has inspired the design of innovations like Bell’s telephone and Velcro.

Lateral thinking in art is exemplified by Salvador Dali and Marcel Duchamp. Surrealism is an inspiration to lateral thinkers everywhere, Paul shows. From the world of architecture, he highlights the creativity of the flying buttress, St Basil’s Cathedral (Moscow), La Sagrada Familia (Barcelona), and Bird’s Nest Stadium (Beijing).

The road ahead

“We can be inspired by and learn lessons from the great thinkers, inventors and innovators of the past,” the author wraps up.

“Become an ideas carrier,” Paul advises. Being willing to help others with creative inputs can showcase your understanding of their needs and leverage your industry networks and lateral thinking abilities.

Lateral thinking helps see new possibilities. “Throughout society, we need smarter solutions to problems large and small. We need lateral thinkers,” Paul signs off.

In sum, this is the perfect book for beginning the new year with a boost of creativity, and a handy reference guide to dip into for rekindling the creative juice.

YourStory has also published the pocketbook ‘Proverbs and Quotes for Entrepreneurs: A World of Inspiration for Startups’ as a creative and motivational guide for innovators (downloadable as apps here: Apple, Android).

![Read more about the article [Funding alert] Mumbai-based nutrition startup TruNativ raises undisclosed seed fund led by 9Unicorns](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Imageqcqs-1618568378744-300x150.jpg)