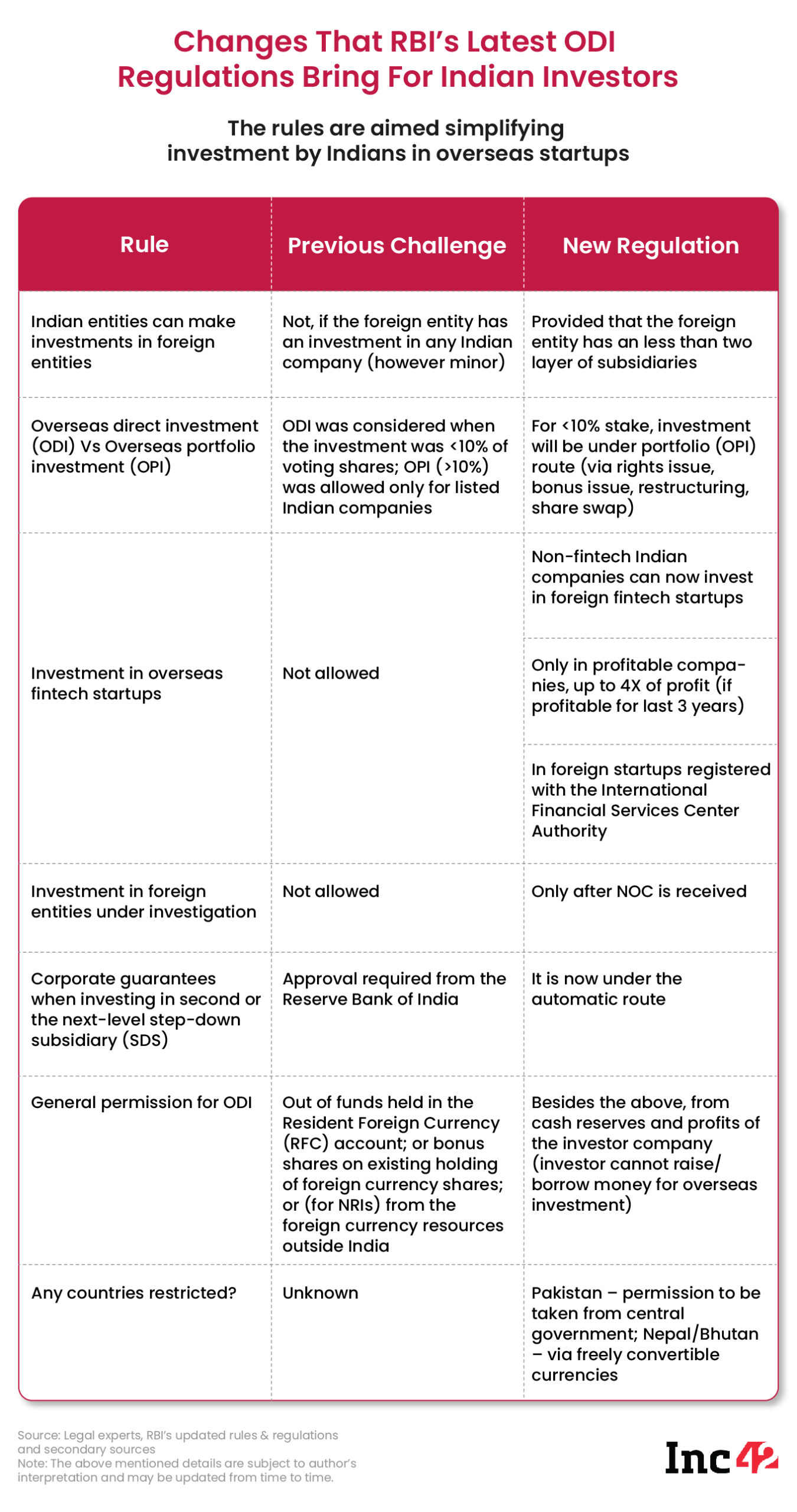

The RBI’s latest regulations have reduced the need for approvals, disclosures and compliances, and automated several actions

Under ODI, the RBI has set a limit of 10% for Indian companies to back foreign startups and brought in the distinction of OPIs

The new regulations also ease the round-tripping structure which earlier restricted Indian investors and companies from setting shop outside India

Last week, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) revised the Overseas Direct Investment (ODI) rules, providing the much-needed clarity on overseas investment.

The new rules outline points that will help Indian startups expand overseas, build businesses in partnerships with foreign startups and allow investors to expand their portfolio, even if there are any overlaps. According to several legal experts that spoke to Inc42, the rules will impact family offices, Indian conglomerates and tech startups opting for ODI in listed and unlisted companies abroad.

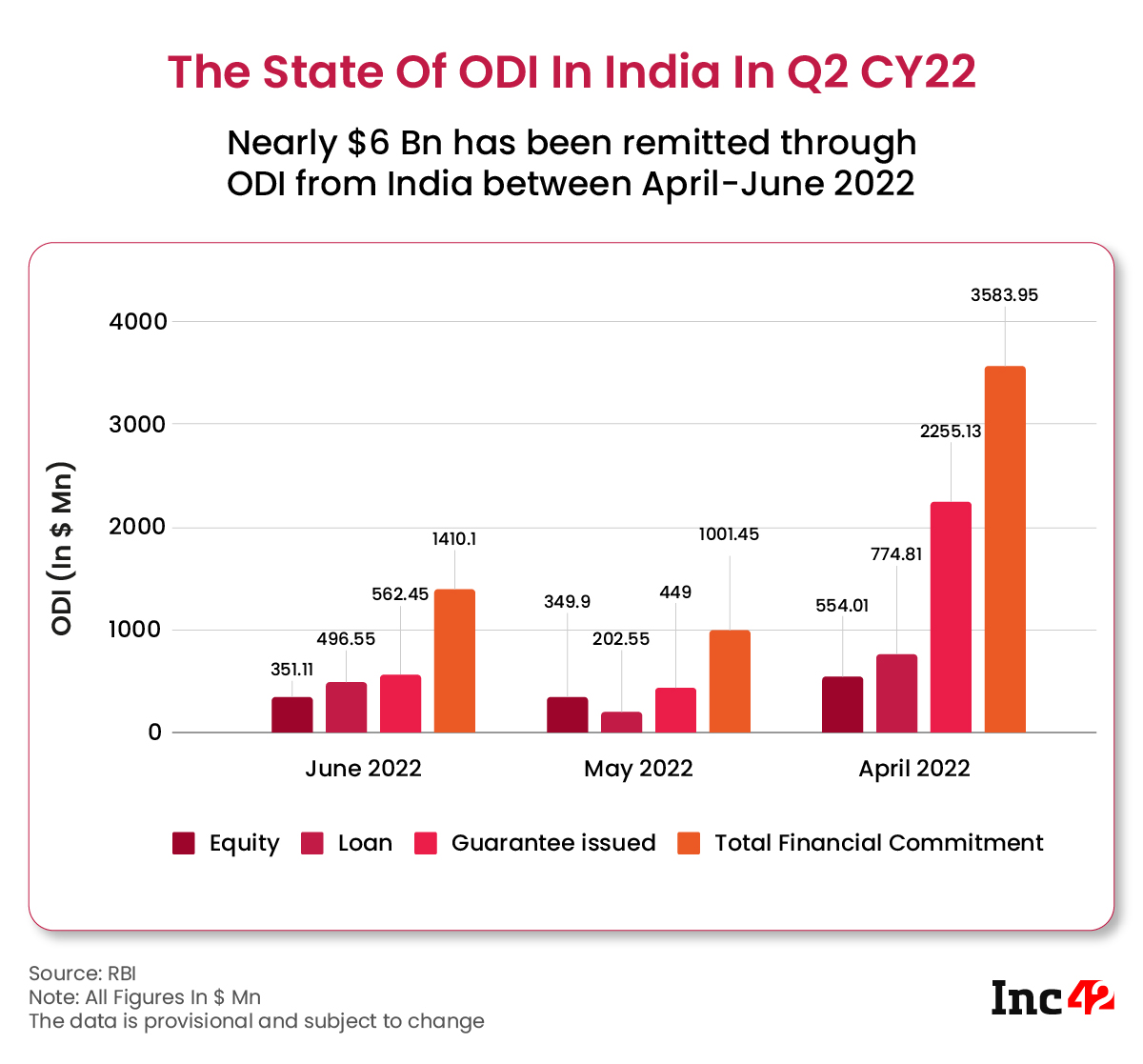

It is noteworthy that in the second quarter (Q2) of 2022 (CY22), nearly $6 Bn has been remitted through overseas direct investments from India, a decline of over 60% from the same quarter last year (ODI remittances stood at $16.35 Bn in Q2 CY21).

While the RBI had been planning for a long time to amend the previous laws governing ODI, the data shows that it became imperative to further simplify the rules to prevent a further decline. Other factors, too, have caused a ‘winter’ within the global funding ecosystem, but it is impossible to overlook the fact that overseas investment had regulatory hurdles.

The revised ODI rules reduce the need to seek specific approvals, compliance burden and costs. For instance, the RBI has introduced a ‘late submission fee’ in case of reporting delays.

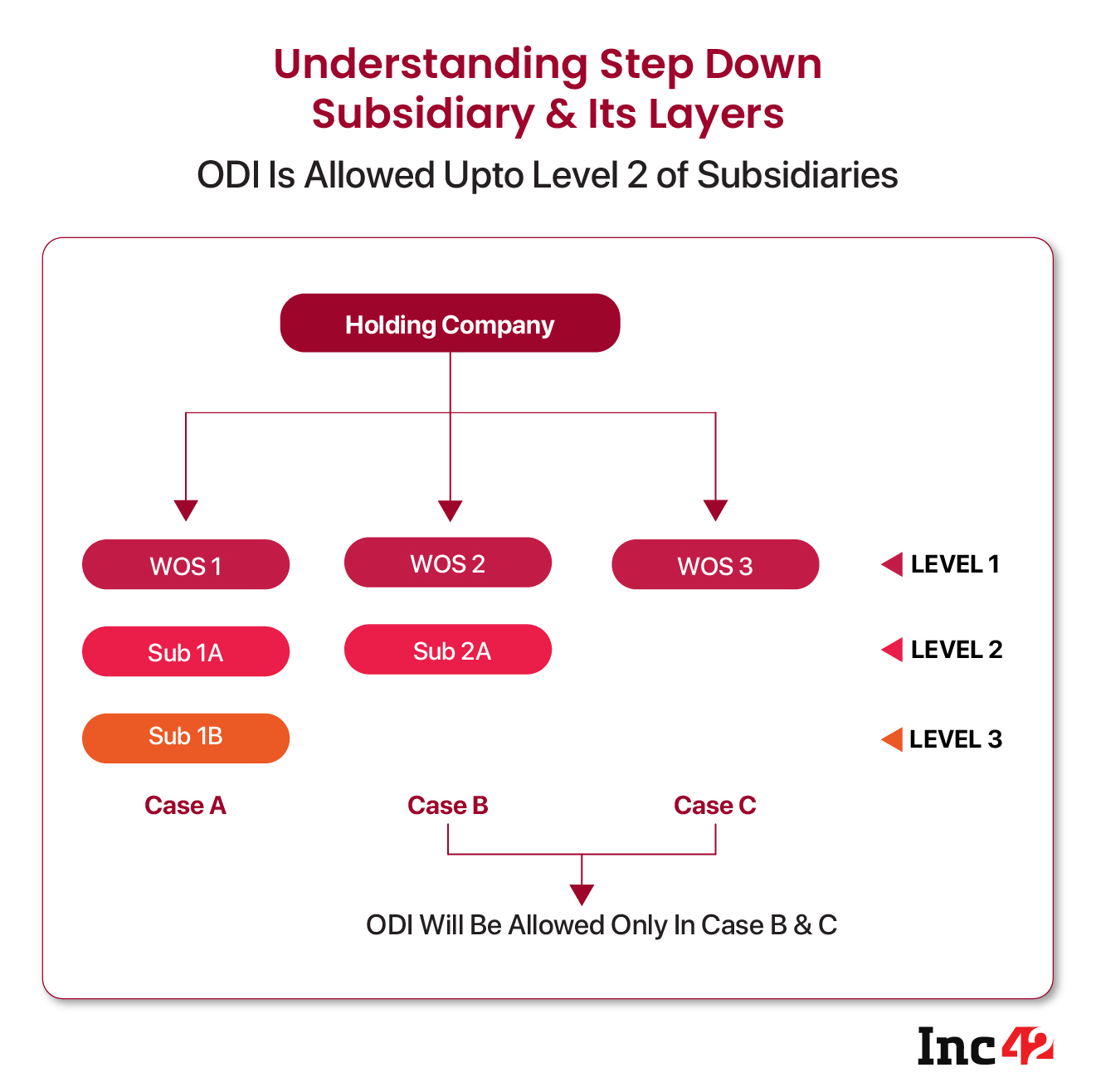

It has also dispensed approval requirements for several activities such as delay in payment of consideration, investment/ disinvestment by Indians into under-investigation foreign startups or issuance of corporate guarantees to step down subsidiaries (SDS) and writing off disinvestments.

Speaking to Inc42, Souvik Roy, Partner at IC Universal Legal, outlined that the definition of ODI was different from the earlier rules. Any investment above the threshold of 10% or that for a controlling stake would qualify as an overseas portfolio investment (OPI), and only listed Indian entities were allowed to make an OPI, he said.

“Under the new regime, overseas direct investment is construed as an investment of less than 10% in any listed entity abroad. However, unlisted Indian entities can also make OPIs in certain cases such as mergers, demergers, rights issues and bonus issues,” Roy added.

Investors can now make an overseas investment for less than 10% stake in the foreign companies without the need for a joint venture. Among other changes, the RBI has made the concept of wholly-owned subsidiaries (WOS) and JV obsolete in the context of overseas investments, the legal experts said.

The Biggest Change – Round Tripping Structures

As per the old rules, Indian companies were not allowed to acquire or invest in a foreign entity that had already made a direct or indirect investment in an Indian company.

For instance, if company A (India) wanted to back company B (US) which had an indirect investment in company C (India), then company A had to go through several regulatory approvals, which the legal experts dubbed as ‘not forthcoming’.

However, as per the revised rules, the round tripping structure, as more popularly known, will not require approval from the central bank if the investee company involves less than two levels of subsidiaries.

“It seems a welcome move to enable Indian businesses to invest in global companies having an Indian presence. It enables Indian investors and promoters to have ‘flip’ structures which are becoming quite prevalent in the Indian startup ecosystem, especially with tech startups,” Roy said.

However, there are some conditions for round-tripping structures.

According to Ashima Obhan, Senior Partner at Obhan & Associates, an Indian resident can make a financial commitment to a foreign entity that has invested in an Indian entity if such an investment does not result in a structure with more than two layers of subsidiaries.

Obhan said that the definition of subsidiary now also includes an element of control. It would ensure the new regulations don’t cover minority investments. Further, it will also mean future direct or indirect investments, as long as there are no more than two levels of subsidiaries, including offshore entities.

The move is of consequence since several foreign startups who wish to set up offices in India end up backing a local company. As Indian startups follow the same route for setting offices globally, the new regulations lift the weight of approvals, disclosures and compliances.

The automatic route within round-tripping investments will benefit startup M&As. The simplification of payment of deferred consideration is a bonus.

One point that remains unchanged is that Indian companies and individuals can only invest in foreign companies recognised by the host country’s governing law.

Opening The Path For Investments In Fintech Companies

Until now, only RBI-registered NBFCs were allowed to do overseas investment in foreign fintech companies or those involved in financial services. Most investors were either not eligible for an NBFC licence or were subject to high compliance requirements.

With certain caveats in place, the new regulations make it easier for individuals or companies to back foreign companies registered with the International Financial Services Center (IFSC). The notable relaxations include inheritance, acquisition of sweat equity shares or minimum qualification shares (for holding a management post in a foreign entity) and ESOPs.

A non-fintech company in India can also invest in a foreign fintech company if the former has posted net profit during the preceding three financial years. However, an Indian entity not meeting the three-year profitability condition may make such an ODI in a foreign entity in IFSC in India, the RBI said. The rules also cap investment to 4X of the profit of the Indian company.

Further, a foreign company will only be a financial services provider if its Indian investment does the same activity and requires registration with or falls under an Indian financial sector regulator.

With the above changes in place, it is safeto say that the government has undertaken reforms to ease both money outflow via ODI (overseas investment by Indians) and inflow via FDI (foreign investments into Indian companies). Yet, certain aspects of the overseas investment rules remain ambiguous, and legal experts are awaiting clarifications from the RBI.