A higher number can spur more aggressive policies to tame global warming, a lower number may make action seem unaffordable.

The United States is updating a figure that experts say could help transform American climate action and reverberate around the world — the price it puts on future damages to society caused by carbon pollution today. That all-important number — the dollar value of the climate change harm attributable to a tonne of CO2 — is known as the social cost of carbon (SCC), or as some have called it, “the most important number you’ve never heard of”. Put simply, a higher number can spur more aggressive policies to tame global warming, a lower number may make action seem unaffordable.

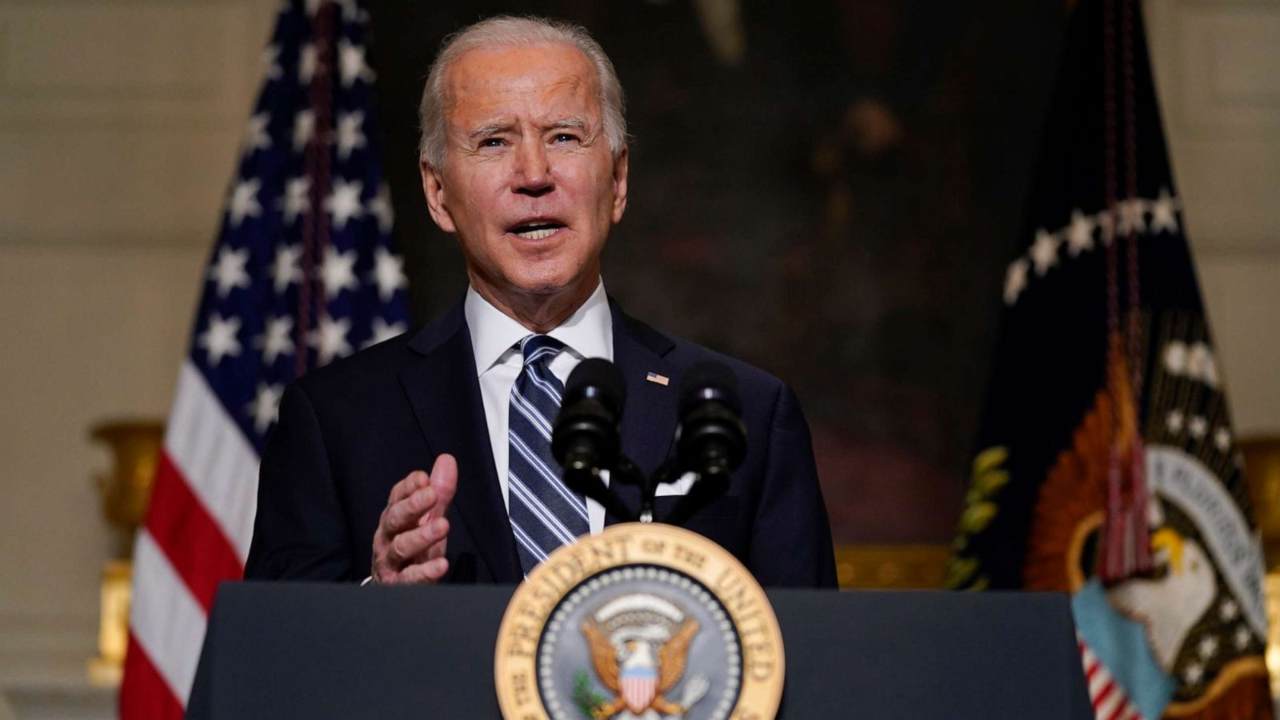

As part of his efforts to resuscitate America’s climate change fight, President Joe Biden last month restored the SCC to Obama-era levels, after the Trump administration slashed it to a nominal amount.

But the new measures are only a first step in a sweeping recalculation, with a final finding to be announced in a year.

Scientists argue the US social cost of carbon must be high enough to reflect the full array of climate effects, from near-term pollution to long-term sea level rise.

Even the possibility of catastrophic shifts in the climate system such as the irreversible melting of permafrost or ice sheets must be taken into account.

Essentially it asks: How much are we willing to pay today to avoid disaster tomorrow?

It considers future illness and deaths from heatwaves, small particle pollution, climate-enhanced natural disasters, property damage, reductions in agricultural production, disruption to energy systems, predicted violent conflicts and mass migration.

“The energy and climate challenge that the world faces is very demanding and we need a guide for how we should be responding to that challenge,” said Michael Greenstone, who was instrumental in coming up with the social cost of carbon under the Obama administration.

In the US, the figure has for years formed part of cost-benefit analyses for everything from power plant regulations to efficiency standards for cars and household appliances, said Gernot Wagner, an expert on the economics of climate risk at New York University.

It was key in calculating US commitments under the Paris Agreement to reduce its carbon footprint.

Powerful signal

But the number has influence far beyond America’s borders.

A recent report from the University of Chicago that Greenstone co-authored said countries including Canada, France, Germany, Mexico and Britain invoked the US social cost of carbon when coming up with their own figures. Some adopted the US estimates wholesale.

The SCC can “influence the direction of international climate negotiations”, the report said.

Nearly 200 nations are set to meet in November for an all-important UN climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland.

An anxious world is looking to the planet’s biggest polluters for stronger near-term commitments for reducing carbon pollution.

“This number that sounds so arcane, is actually a very powerful piece of information that can help improve our climate policies,” said Rachel Cleetus policy director and lead economist for the Climate and Energy Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, adding the SCC could also be a “powerful market signal”.

Magic number

Biden’s working group of experts came up with a place-holding figure for the social cost of carbon of $51.

But they stressed their estimates — which include separate metrics for methane and nitrous oxide — “likely underestimate societal damages”, leading to speculation that the final figure could be substantially higher.

Under Trump, the number was hacked back to as low as $1, a move “difficult to justify based on science and economics”, the University of Chicago report said.

It did, however, enable a roll-back of environmental regulations, including stringent fuel economy standards for vehicles.

But restoring the social cost of carbon to earlier levels is not good enough, experts say.

Using the Obama-era measure, for example, climate damages linked to extracting coal from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming are still six times larger than the coal’s market price, Greenstone said.

A more substantial SCC reflected in government policies, he added, “would turn an activity where people were actively bidding to access those resources into one where people didn’t want to bid for it”.

He says the social cost of carbon should be immediately doubled to $125.

This revision was made by cutting what economists call the “discount rate” — which determines how much the value of future climate damages are marked down — from three to two percent.

There is a growing case for reducing the discount rate in order to assure what Cleetus called “intergenerational equity”.

“In this case we’re not talking about your college fund or something like that, we’re talking about planetary health,” she said.

Moral imperative

A decade of new research has dramatically broadened our understanding of the real costs of carbon pollution, including inequalities within and between nations and the impact on health.

For example, mortality associated with climate risk was underestimated in the last SCC calculation by at least an order of magnitude, according to recent findings.

In December the Lancet medical journal warned that a deadly mix of extreme heat, air pollution and intense farming created the “worst outlook for public health our generation has seen”.

This is not just a future scenario.

The five hottest years on record have all occurred since the 2015 Paris deal was inked.

This has stoked monstrous wildfires in America, Australia and Siberia, while warming and rising seas have amplified storms, including last year’s record number of Atlantic hurricanes.

The world’s 10 costliest weather disasters in 2020 caused insured damages worth $150 billion, according to the charity Christian Aid, which said the true cost was far higher.

In the US alone there were an unprecedented 22 separate billion-dollar weather disasters.

John Kerry, in his first address to the World Economic Forum as US special envoy for climate action, suggested the world is on a war-like footing.

“We are here now in this moment, not just because we understand the urgency, or because we understand the moral imperative,” he said. “We are here because we know we can’t afford to lose any longer.”

Here and now

The US — the world’s second-largest carbon emitter — has rejoined the Paris Agreement, which calls for capping global warming at “well below” two degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, with an aim for a less-damaging 1.5C.

Can the social cost of carbon help reach that goal?

Leading economists Nicholas Stern and Joseph Stiglitz warned in a recent report that “flaws” in the way it is calculated could lead to a dramatic overshoot of the Paris limits.

They argue the process should be flipped: start with the 1.5C target and work backwards, figuring out what levers are needed to get there.

But Wagner said this would only work in countries where governments embed the target into law, as in Britain.

“More important than the specific number is re-establishing a scientifically and economically credible process,” that can endure changes in government and legal challenges, he told AFP.

There is consensus on one point: climate action needs to go much, much further.

“It’s here and now. It’s costly. And it is a big threat,” Cleetus said. “By ignoring this signal we are taking decisions that are actually worsening the harm, today and for future generations.”

Subscribe to Moneycontrol Pro at ₹499 for the first year. Use code PRO499. Limited period offer. *T&C apply