In the early days of a startup, it is comparatively easy to make prioritisation choices as founders and product people work closely. But the scenario changes drastically when the company scales up

Vikrama Dhiman, a product leader at Gojek who will speak at The Makers Summit 2021, says, “All prioritisation frameworks miss two crucial things. It takes longer to build and you usually get a lower impact than what documents suggest”

Tying the prioritisation framework to PMs’ performances and a company’s revenue goals is an effective way to monitor the product strategy, but the most important objective of a framework is to decipher how well a user is being served

One of the fundamental problems that every technology startup faces is prioritisation. What features to build first, which user cohort’s needs must be met at the earliest or the bug fixes that must be done without delay are some of the most pertinent issues every product leader has to resolve every day.

In the early days of a startup, it is comparatively easy to make these choices as founders and product people often work together. But the scenario changes drastically when the company scales up. For instance, in the early days, a one-person product team will architect the product, take it to the engineering department, get it developed, launch it and iterate it based on feedback.

In brief, everything is done single-handedly. But when the team grows and, say, two people are thinking about the same problem, there is an added element of communication between them. This increases the resolution time, be it bug-fixing or developing a new feature. Most importantly, each person may perceive the priorities differently, and hence, each task may take even longer than anticipated.

According to Tejas Vyas, the product head of online grocery behemoth BigBasket, “With more people (in the team), your efficiency comes down exponentially. If two people solve the same problem, you do not get 2x more efficient but around 1.5 times. Similarly, when four people come in, you get 2.2x efficiency. Unfortunately, that is the reality, and that is how the world works, not just BigBasket alone. And we have to keep it in mind when working on prioritisation.”

Choosing The Right Prioritisation Framework

There are many prioritisation frameworks, but a few are widely popular. So, let us take a quick look at those:

- The RICE model requires evaluating the reach (number of users affected), impact (how important the feature is in the context of the entire product), confidence (the probability of achieving the desired objective/s) and effort (the time taken by the product, design and engineering teams to implement it).

- The Kano model, created by the Japanese researcher Noriaki Kano in the 1980s, highlights five categories — the must-haves which make the product functional, the features users may not ask for but will feel disappointed if these are not included, the bells and whistles which make a product attractive, the features towards which users are indifferent and those which can make a negative impression on users.

- The MoSCoW model involves categorising all features according to decreasing order of importance — must, should, could and would, to be precise.

Understandably, different products and companies have unique requirements, and these prioritisation frameworks may not fit the bill every time. A young company may start out using one of the popular frameworks, but product leaders will eventually spot the deficiencies and create their custom frameworks.

For instance, the mobility arm of the Indonesia-based super-app Gojek has created the ICISI framework for prioritisation. The ‘I’ denotes impact (improving customer experience and aligning with a company’s mission instead of just looking at the problems or the effort). The ‘C’ stands for company themes for the year and the long-term group visions, which translate into individual team goals and the chronology in which these will be pursued. The ‘I’ in the middle refers to the research, design and technology involved in the process. The ‘S’ implies sharing the backlog with all stakeholders. And the ‘I’ at the end means inspecting the goals every month to adapt to business needs.

Vikrama Dhiman, a product leader at Gojek, writes in a blog that “All prioritisation frameworks miss two crucial things. It takes longer to build and you usually get (a) lower impact than what documents suggest.” According to him, a product manager should always underestimate the intended impact on a user by two-thirds and assume that it will take three times the planned effort to build it — this will help reject many of the weaker iterations.

Marshalling The Product Function With Prioritisation

Gojek’s product function faced a crucial problem in the early days; it was all about prioritisation in individual silos. Every team had its specific goals, which created considerable friction in aligning the goals of different product managers and teams. This resulted in a lot of discussions which took weeks and months to resolve.

“We fixed this by identifying the company themes which all teams have to support as P0 (highest priority). Also, teams had to align with each other on a quarterly basis, based on dependencies. This has fixed the problem of individual silo prioritisation to a large extent,” says Dhiman, who will be a speaker at The Makers Summit 2021. The virtual event, to be hosted by Inc42 on March 12-14, will be attended by 10,000+ product, marketing and design folks.

Register For The Makers Summit

The process implemented by Gojek to resolve the prioritisation issues works like this:

- Tracking the priority of requests from other teams and requests to other teams (using Asana)

- More visibility for executives into what each team is doing through demos

- Having a long-term vision document for each team besides charters directly impacting customer experience or IPO goals. If there are no correlations, those goals are not picked

- Setting up ‘saying no to things’ as a principle

For the hyperlocal delivery company Dunzo, the first step of prioritisation is not a framework that evaluates the impact on users and the resources required to achieve it. “The first critical input for us is user, partner and merchant requests gathered from support tickets, Playstore and social media reviews, panels of representative users and the net promoter score (NPS) feedback,” says Anirban Das, head of Dunzo’s product function.

The ICE (impact, confidence, effort) framework comes as the second input, where the impact is calculated based on how each task will influence the company’s revenue goals. Finally, features are broken down into experimental and slam dunk, based on how confident the product team is about improving user experience with the help of those.

It is okay to take a few shortcuts in the experimental bets as validating the hypotheses is more important than perfection. For the slam dunk bets, Dunzo’s product team sets a longer time horizon to avoid rework in the near term.

Why is each leg of the prioritisation process firmly tied to metrics?

“All product managers (PMs) are evaluated based on the metrics and the key performance indicators (KPIs) we use in our prioritisation framework. Performance reviews of PMs are based only on how we do against these metrics and KPIs,” says Das.

Akash Gehani, cofounder and COO at Instamojo, concurs, saying that metrics should drive the frameworks entirely and be tied to PMs’ performance indicators. “It is always about revenue or usage and NPS. In fact, the frameworks can impact performances or KPIs in a big way. Hence, it is critical for anyone responsible for the KPIs to be involved in and aligned with the framework. It is imperative that all teams and members understand why particular tasks are being prioritised. Otherwise, it will lead to confusion or dissatisfaction in the longer run.”

Register For The Makers Summit

Using Prioritisation To Achieve North Star Metric

Tying the prioritisation framework to PMs’ performances and a company’s revenue goals is an effective way to monitor the product strategy. But the most important objective of a framework is to decipher how well a user is being served.

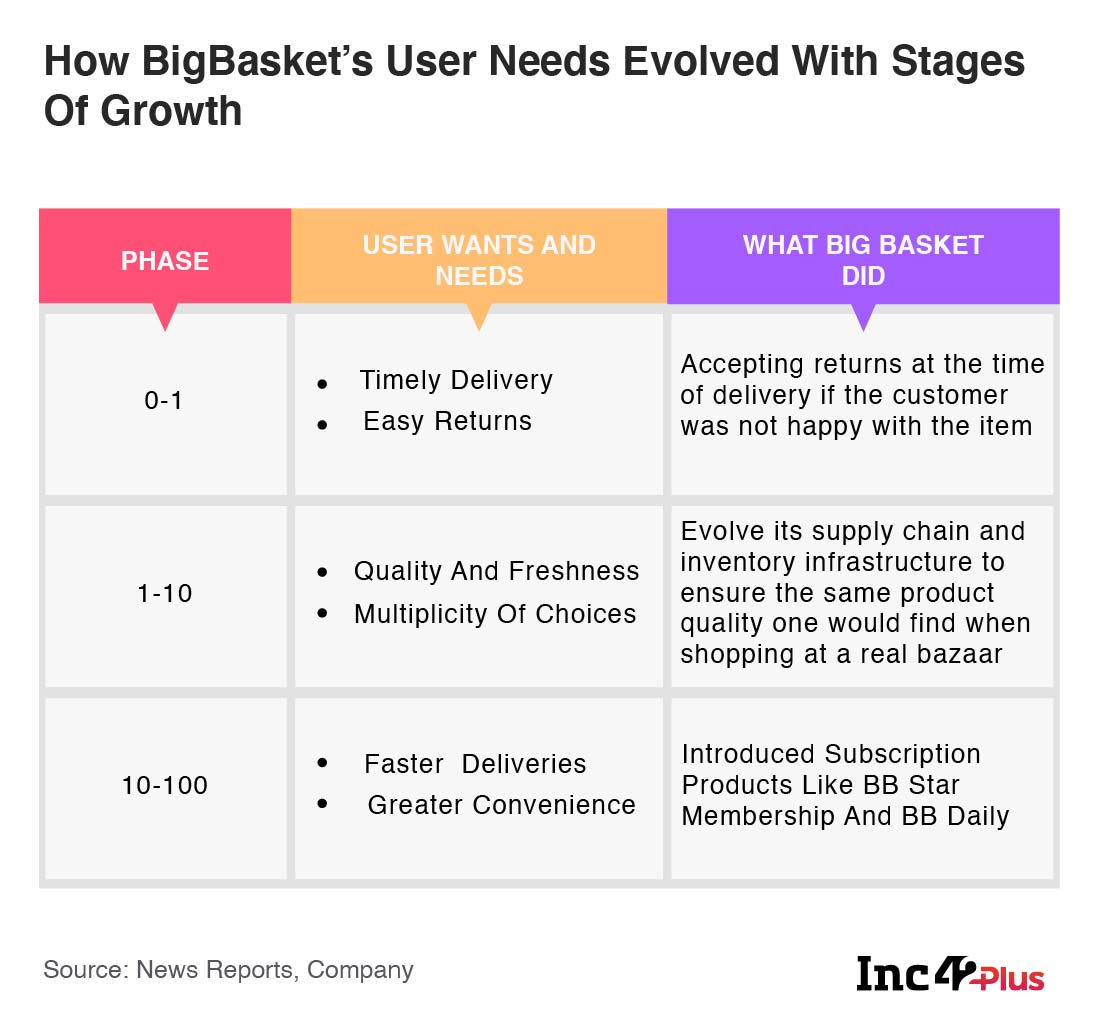

Online grocery company BigBasket had realised this early on. In fact, the absence of prioritisation was a major reason behind the technology-related issues that the company faced in the initial years when most startups focus on fast growth and viable unit economics.

Having witnessed the consequences as one of the first engineering leaders, BigBasket’s product head Tejas Vyas takes it seriously as he gets daily requests from every team to tweak or build new features and products.

The focus on prioritisation has led to a fast-evolving product development process that asks at every point what a customer’s needs are in real life. Vyas refers to the paradigm as the market-product fit instead of the much-jargonised product-market fit to underline its importance. The reversed nomenclature helps reiterate that the market’s demand is the primary driving force behind a product and not the other way round.

In a bid to achieve the market-product fit, the online grocery platform has developed a unique framework called WWWH (who, why, what and how) that decodes the most critical pain point in a market and the best approach to solve it.

The product folks at BigBasket have deciphered that the biggest need of a customer ordering groceries online is getting all the products she/he has ordered (imagine planning a pesto pasta lunch but the pesto gets left behind). Also, getting the items on time is equally important – the designated time slot is mostly sacrosanct.

This is why the company has adopted the WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) method as its North Star or the guiding metric. The primary value proposition of a delivery company could be faster deliveries. But for BigBasket, it has to be the assurance that customers will receive everything they have ordered, and the WYSIWYG metric has been developed to measure this function.

According to Vyas, this percentage is always maintained above 99.6%. Even when Covid-19 lockdowns disrupted supply chains, the figure hovered around 98%, falling by 1.6 percentage points from the company’s usual threshold of tolerance. However, customers were okay with even 60% of the cart order, as most people were desperate to get whatever they could.

“If a customer orders ‘X’ number of items, we will try to deliver all of them. That is the basis of the whole business model at BigBasket and the WYSIWYG metric attached to it. There might be other platforms where people order and WYSIWYG might not be their value proposition. But we believe that customers want all the items they have ordered and optimum order fulfilment remains the most crucial criterion even when they are ordering online,” says Vyas.

Register For The Makers Summit

![Read more about the article [Funding alert] Spinny raises $248M, turns unicorn](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/spinny-p-1626688440721-300x150.png)

![Read more about the article [Jobs Roundup] Work with Bengaluru-based fintech startup Khatabook with these openings](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/khatabookteampicture21569840696854jpg-300x150.jpeg)

![Read more about the article [The Outline By Inc42 Plus] New Breed Of Big Tech In India](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Outline-97-_Social-300x157.jpg)