Indian consumers, traditionally seen as price-conscious, are showing a growing appetite for premium items across a range of sectors, from real estate to smartphones and luxury hotels. The trend, documented by AllianceBernstein analysts in a note to clients this week, signals a shift in the spending habits in the world’s most populated nation that has attracted over $70 billion in venture capital and emerged as a key market for several American tech and entertainment giants in the past decade.

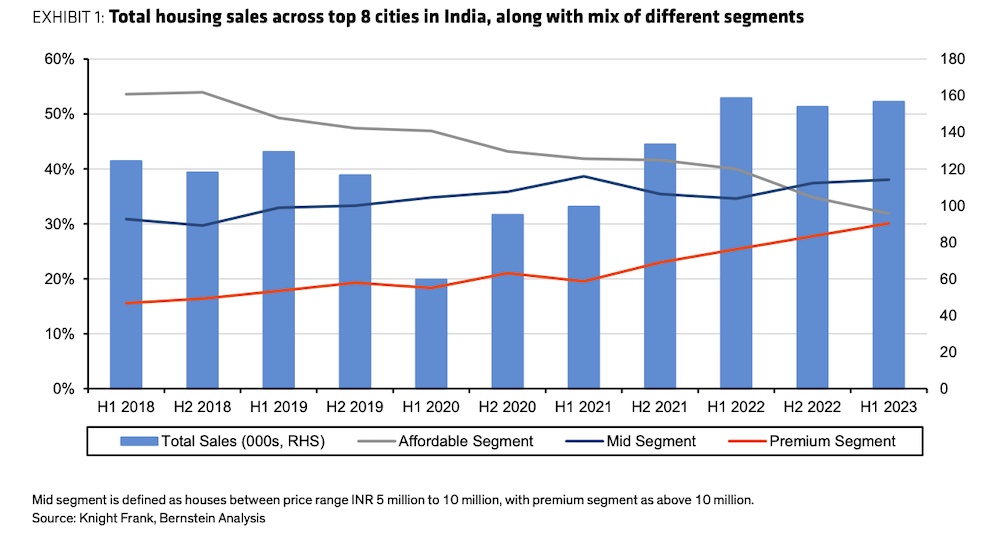

Autos and houses have evolved from mere necessities. Now, they symbolize aspirational living standards for a segment of the upper middle class. In the property sector, there has been a notable shift. The share of premium properties priced above 10 million Indian rupees in top cities has doubled, moving from 15% to 30%.

Luxury hotels are similarly experiencing a surge in bookings, with room rates seeing an upward trend.

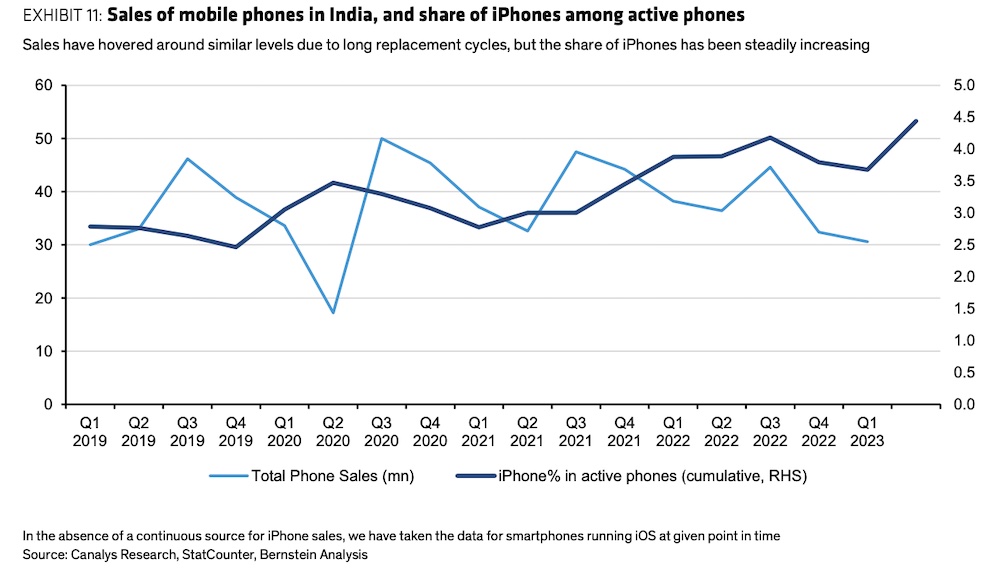

During the first quarter of 2023, the smartphone market witnessed a significant transformation. Shipments of smartphones priced below $400 have decreased. Conversely, the premium and ultra-premium categories have seen a substantial 60-66% boost.

Across the personal vehicles category, there’s a pronounced lean towards SUVs. Entry-level cars, which once constituted 60% of the market in the 2000s, have dwindled to 25%. The motorcycle segment is also reporting a rise in the popularity of mid to premium range bikes.

Consumer durables have transcended their original utilitarian roles. Today, they often serve decorative and aesthetic purposes in households. Premium fans are at the forefront of this growth, and there’s a significant uptick in inverter AC sales.

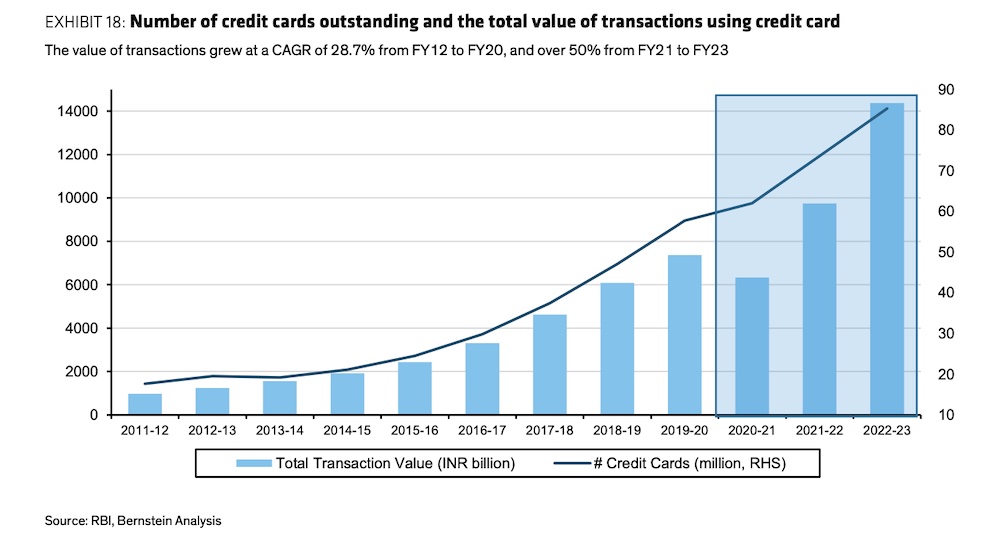

Analysts at Bernstein believe that the increasing income levels and the behavioral and financial shifts spurred by COVID have been the pivotal moments in the Indian consumers’ transition towards premium products. They also argue that easier access to credit appears to have contributed to the shift.

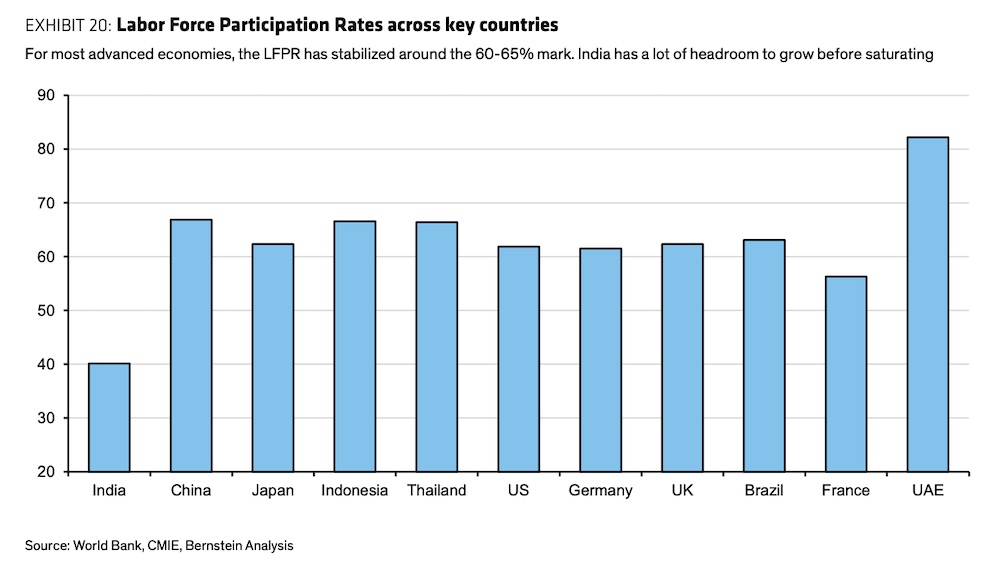

One key thing that India needs to solve to maintain — and supercharge — the growth is improving its current workforce participation, which sits at 40%.

“There are challenges in achieving that number, as female labour force participation is abysmally low, so without the contribution from both genders, the numbers are unlikely to go past 50%. Moreover, even with increased labour force participation rates, India’s productivity may not see the rates of advanced economies since issues of disguised unemployment will arise with a large part of the workforce being employed in agricultural activities,” the analysts wrote.