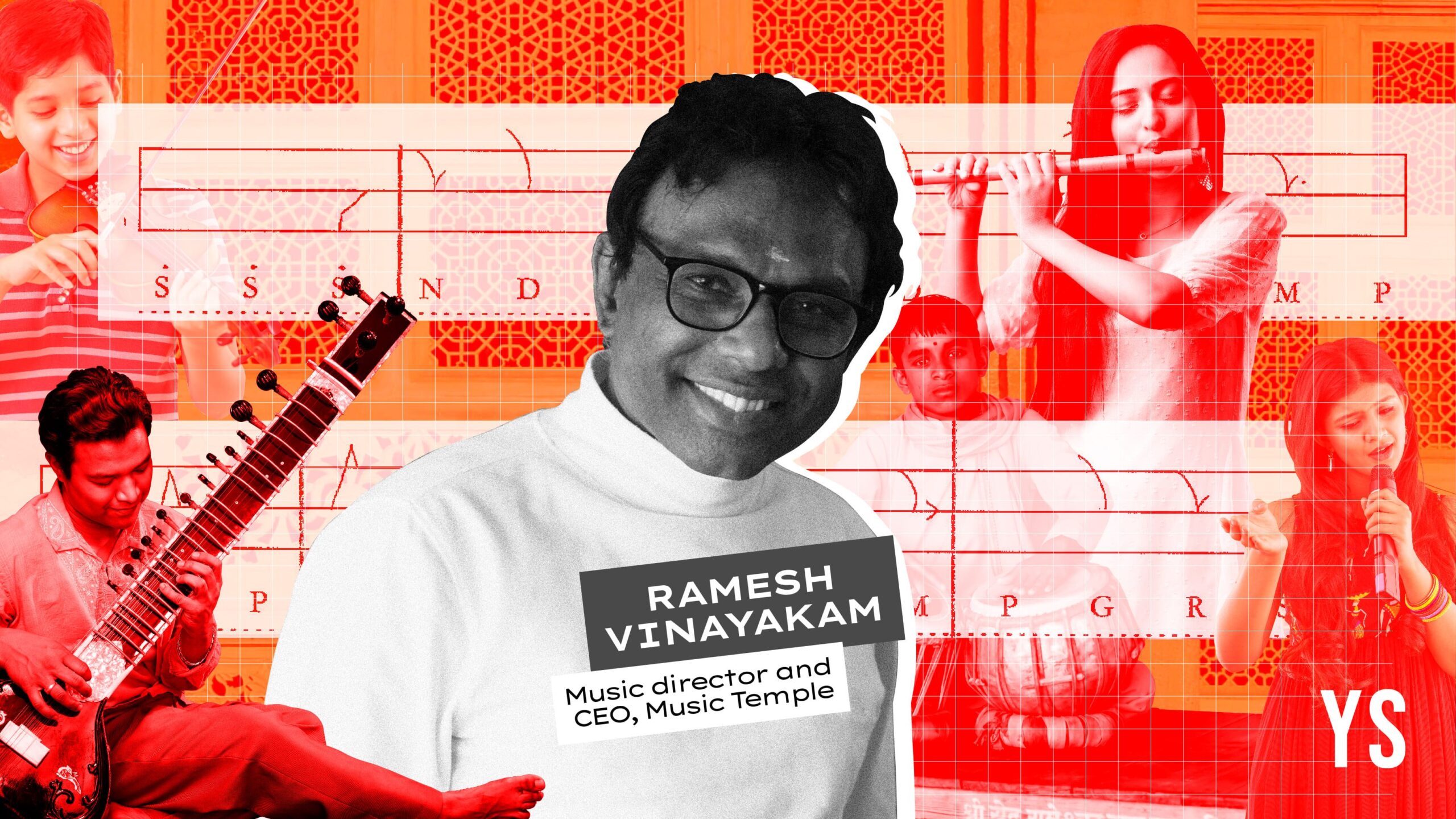

With the temple’s speakers blaring music a little too loudly, Ramesh Vinayakam steps outside to find solace under a nearby tree. The setting is perfect—late evening with green fields stretching to the horizon, and heavenly Carnatic music being performed live in the background.

As he settles down, his gaze drifts to the road. He notices a haggard-looking cyclist approaching. The man, clad in a printed lungi, dismounts near him, pulls out a beedi, and lights it with practised ease.

Taking his first puff, the cyclist looks towards Ramesh, nods in the direction of the temple, and asks him in Malayalam, “Anandabhairavi elle?” (Isn’t the singer performing the Anandabhairavi raga?)

This episode, which took place over 30 years ago in Kerala, reiterated Ramesh’s long-held conviction that the appeal of Indian classical music is limitless. If a beedi-smoking cyclist on a deserted road can correctly identify a complicated Carnatic raga like Anandabhairavi, then surely the common people possess a latent understanding of and appreciation for this art form, deserving wider access to its teachings.

There was one issue, though. The prevalent method of teaching relied heavily on one-on-one interactions between the guru and the disciple, which couldn’t be scaled up. This approach limited the number of students who could be reached, and placed immense stress on the gurus, who had to sing every note of the raga numerous times throughout the day.

Ramesh, a trained Western and Indian classical musician himself, knew even then that the way forward was through a notation system that students could read and practise on their own, even when the guru was not around. But there was a catch.

Unlike Western classical music, where each note is played with precision and consistency, Indian classical music relies heavily on gamakas—an essential and expressive form of embellishment. These intricate oscillations and variations in sound add nuance, depth, and emotion to a note or phrase. The fluid nature of gamakas, with their subtle shifts in pitch and tone, makes them difficult, if not impossible, to accurately capture through traditional musical notation on a sheet of paper.

“So Western music is the point-to-point movements of swaras (musical notes)… They move from one step to the other from the centre,” says Ramesh. “Whereas with Indian music, how do you actually write all the intervening oscillations and movements? It cannot be written that way (the Western method).”

To use an analogy, gamakas in Indian classical music are like the graceful curves and flourishes of calligraphy, where each stroke carries subtle variations in pressure, speed, and direction, giving the writing a dynamic, expressive quality. These embellishments add layers of emotion and meaning to the notes, making the music feel alive and deeply personal.

In contrast, Western classical music is more like finely printed text, where each letter is clear, precise, and uniform. The beauty lies in the structure and arrangement of the words, but the individual letters remain consistent and unadorned.

To be clear, Indian music has a notation system but that is extremely basic and not enough to capture the breadth of its beauty and range.

In the couple of decades since the encounter with the solitary cyclist, Ramesh went on to become a musician of repute, composing songs and background scores for several South Indian films, including Nala Damayanthi, which was produced by thespian Kamal Haasan and starred R Madhavan.

Despite his success, he never forgot his dream of seeing Indian music reach its full potential through wider and easier access. He remained committed to finding ways to make classical music more accessible to all, believing that its beauty and depth should not be limited by traditional teaching methods or geographical constraints.

A breakthrough

In 2010, Ramesh was writing a cover story on the legendary violinist VS Narasimhan for Sruti magazine. Narasimhan, a key figure in establishing the Madras String Quartet, was known for his elusive nature with the media. So, securing this interview was a rare achievement—a coup in the world of South Indian classical music journalism.

As the interview progressed, Ramesh felt a familiar question forming on his lips, one he often posed to the serious Indian musicians he met: When will the Indian music tradition develop an effective and efficient notation system of its own? However, just as he was about to ask, he paused, overtaken by a sudden and intense realisation. A thought, almost like a whisper in his mind, urged him to consider something he hadn’t before: Why not invent the notation system yourself?

In that fleeting moment, it was as if a voice had spoken directly to him, clear and unwavering: Among the rocks, the diamond is there. It’s time you find it. This inner calling was so powerful that it left him momentarily speechless. From that moment on, Ramesh knew his path was set. He was meant to be the one to discover this “diamond”—a notation system that could capture the full essence of Indian classical music.

Ramesh, driven by the sudden clarity of his revelation, looked Narasimhan straight in the eye and declared, “Sir, I will invent a notation system for Indian music.” Narasimhan, caught off guard by the unexpected statement, raised his eyebrows in surprise. But being the gracious person he was, he remained silent for a moment, absorbing Ramesh’s bold proclamation. Then he nodded slightly and continued with the interview, answering the other questions as if nothing unusual had been said.

This no-nonsense musician followed his inner calling to create a notation system that strives to capture the full essence of Indian classical music. His journey has all the ingredients of any startup founder’s story.

What Ramesh didn’t know then was that the path ahead would lead him into entrepreneurship, turning him into a startup founder on a journey filled with doubts, obstacles, and moments of sheer frustration. This is what any founder attempting a moonshot project faces—the potential returns could be massive, but were the risks truly worth the pain? His vision was clear, but the road ahead promised more uncertainty than guarantees.

For Ramesh the subsequent days were a blur. Consumed by the idea of developing a notation system for Indian classical music, he neither ate on time nor slept enough hours. He hardly remembers what happened during that period and describes himself as being like a man possessed, entirely focused on his mission.

His wife, Srividhya, remembers this phase. She recalls it vividly—how Ramesh didn’t return from his music studio one day, prompting her to go looking for him the next morning with some food.

“So, I went to the studio and asked, ‘What happened?’ He replied, ‘I have got a brilliant idea, don’t disturb me for some time, please.’ This continued the next day, and the day after that. It soon became like a sort of tapas (penance) for him,” says Srividhya, who was a theatre actor—often playing the iconic role of ‘Mythili’ in the dramas of the famous ‘Crazy’ Mohan troupe—before taking a break after the birth of their two sons.

In fact, it was during one of the drama performances that they first met in the early 2000s. Srividhya, who worked at a bank and performed as a stage actor for passion, and Ramesh, the no-nonsense musician deeply rooted in his craft, fell in love and married soon after.

Even though Srividhya was accustomed to the quirks of a creator, this time felt different—much more intense. Ramesh was so consumed by his work that he needed medication just to sleep. Sometimes, even that didn’t help.

“And finally, one day—I remember it was early in the morning—I had this three-line thing,” Ramesh recalls, referring to the notation system he invented, which is structured on three lines [see graphic]. “That was the eureka moment. Then I knew it was possible. It was only the very, very, very smallest of sparks, but a spark nevertheless.”

Ramesh rushed home, eager to share his discovery with his wife, but her reaction was lukewarm.

“I am not someone with deep musical knowledge. I have a musical sense, but that’s different from truly understanding it in depth. I didn’t quite grasp what he was telling me,” Srividhya admits. “I was like, ‘Did you really spend all this time on this?’ And, as a mother of two with so many responsibilities and financial commitments, it was natural for me to react that way.”

For Ramesh, the feeling was mixed. “It was fear and happiness together. Because music is an ocean. Now I am starting with the possibility. But can it [the notation system] really do everything? Am I good enough for that? I mean, I am small and music is an ocean,” he says.

While Ramesh was eventually able to convince his wife of the uniqueness and importance of his notation system, the larger Indian music community was not as receptive. Except for a handful of individuals who understood and appreciated his new notations, everywhere else he went, he faced rejection—and sometimes even outright humiliation. Musicians and scholars were sceptical of his idea, dismissing it as unnecessary or impossible. On top of that, Ramesh needed funding to test his hypothesis, but support seemed out of reach.

It was during this difficult period that fate intervened. On the sidelines of a Carnatic concert in Chennai, Ramesh happened to meet Shriram Group Founder R Thyagarajan.

Entrepreneur, patron, visionary

Thyagarajan, 87, is an unconventional tycoon whose business acumen is matched only by his philanthropic spirit. A mathematics graduate turned financial innovator, Thyagarajan built a multibillion-dollar empire by lending to India’s unbanked population, proving that serving the poor could be both socially impactful and profitable.

His approach to business is deeply rooted in socialist principles, yet guided by market forces. Thyagarajan’s modest lifestyle—he drives a small hatchback and lives in a simple house—belies his substantial influence in India’s financial sector. In a remarkable act of generosity, he gave away shareholdings valued at over $750 million to his employees.

Known for his analytical mind and willingness to challenge conventional wisdom, Thyagarajan began understanding the nuances of Carnatic music at a very young age.

Even at 5, he could identify complicated ragas. Though he never pursued music as a career, preferring to let others do the “hard work,” he remains a devoted aficionado and patron of the arts.

In a rare interview with YourStory, Thyagarajan says that his understanding of classical music began by listening in on the lessons given to his elder sister when they were kids.

“See, what happens is, in those days, at least in Brahmin households and the households of reasonably well-to-do people—even Chettiars and Mudaliars [both affluent communities in Tamil Nadu]—learning music was mandatory for girls whether they liked it or not,” says Thyagarajan, seated in the meeting room of one of his offices in a posh Chennai neighbourhood. “There would be a music teacher, so they’d come and teach. And I happened to be in the house, so I could catch as much of it as my sister could.”

He adds with a chuckle, “She was two years senior to me. She was learning, but not very enthusiastically because it was mandatory for her. For me, it wasn’t. So I could learn easily. That’s the difference. If you make something compulsory, people don’t like it.”

But Thyagarajan was hooked. While he appreciated all performers initially, he realised he was becoming much more choosy about whom he listened to when he moved to Kolkata (Calcutta then) to study at the prestigious Indian Statistical Institute.

“So when I came to Calcutta, I was fairly well grounded in classical music—Carnatic music, and a familiarity with Hindustani music. And thereafter my listening became a bit critical. Critical based on criticism. I wouldn’t like to listen to any music, I became choosy: Which is really good classical music? Which is ordinary classical music?” he says.

“I had settled down to listening to Carnatic music only through Lalgudi Jayaraman’s music… I became a Lalgudi Jayaraman fan.”

Lalgudi Jayaraman was a legendary Carnatic violinist, vocalist, composer, and guru known for his unmatched virtuosity and innovation in the art form. His unique style, often referred to as the “Lalgudi Bani,” set a new standard in both solo and accompaniment performances in Indian classical music.

Thyagarajan’s love for music continued throughout his life, and he became a patron and supporter of those willing to make a difference. When Ramesh met Thyagarajan in 2015, he had already heard about the composer’s efforts to take Carnatic music to a wider audience.

“Somebody introduced me to him [Thyagarajan), and he said, ‘Oh, I know, I’m following you’… I was very surprised because I didn’t know him personally,” reminisces Ramesh about that fortuitous meeting.

Thyagarajan asked Ramesh what he could do to help his cause, and Ramesh mentioned the need for funds. Thyagarajan promptly wrote him a cheque.

When asked why he decided to back Ramesh, whom he didn’t know personally, Thyagarajan says, “He is an extraordinary chap. I mean, intellectually, if you look at his intelligence level, it is very, very high. His intelligence would have made him known in any field that he might have entered. But he had a passion for music… In spite of all kinds of lack of enthusiasm and support around you, he has stuck to it, and that is determination and commitment. Passion. There are many words that you can use.”

Ramesh says the trust shown by Thyagarajan made him feel extremely responsible. Once, when he went to show him the accounts for the expenses incurred, Thyagarajan told him not to do so, adding, “Only come and see me if there is something wrong and you need help.”

Ramesh Vinayakam found a strong ally in Shriram Group Founder R Thyagarajan, who had immense faith in the musician’s ability and intelligence.

With Thyagarajan’s support, Ramesh transformed his wife’s music school into the Music Temple Academy, set up a small office, and employed a few musicians to fine-tune the Gamaka Box Notation System he invented. The ‘box’ in the name refers to the notation’s structure, where each set of notations appears within a box.

Within a few years, the system was perfected, but even then, very few traditional musicians accepted it. Many purists argued that the soul of the music would be lost in translation. “No one was convinced. Actually, many of his own friends [in the music fraternity] were not convinced. But it’s a fact that any invention takes effort,” says Srividhya.

Ramesh says the lack of acceptance was surprising. “There were doubting Thomases, those who held on to age-old convictions, rank incredulousness and dismissive attitudes,” he says. “I never expected that as a musician. Because I come from the film industry and there, if something is new, we actually grab it.”

Exasperated, Ramesh had congenitally deaf individuals play Carnatic music through his notation system to prove it worked. Even then, the classical music community did not warm up to his invention. Reflecting on the experience, Ramesh says it left him wondering, “Who is deaf?” The one who cannot hear, or the people who can’t identify the effectiveness of an innovation when it screams its possibilities at you?

A global audience

Halfway around the world, Jeremy Woodruff travelled to India in the early 2000s to understand and learn Carnatic music. Growing up in a Beatnik/Hippie household in Boston, his parents had introduced him to Hindustani classical music at an early age. Later, when Jeremy first encountered Carnatic music, he immediately felt a deep connection and wanted to explore it further.

“For me as a musician, it was clear that the virtuosity in Carnatic music is very, very different from Hindustani music,” says Jeremy, 51, a Western classical musician and Senior Scientist at the Doctoral School for Artistic Research at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz in Austria. “And so, I was immediately very interested and drawn to it.”

In 2004, his quest to understand both Carnatic and Hindustani music brought him to India. Though he managed to grasp the basics, he couldn’t go deeper due to the traditional methods and time-intensive approach to learning Indian classical music.

“I learned a couple of ragas… a varnam [a type of composition that has all the key features of a raga], but after three months in India, I had made only a little progress. It was frustrating because I couldn’t gain a larger perspective,” says Jeremy, who was accustomed to reading notes, unlike the traditional Indian method of learning through repetition.

Speaking via video chat from Austria, he adds, “It seemed completely inaccessible for me, especially as an outsider, because of the sheer amount of time and effort it required.”

When Jeremy returned to India to teach at AR Rahman’s KM Music Conservatory in Chennai, he came across Ramesh and his Gamaka Box Notation System. He was looking for “some alternative ways of learning Carnatic music that could give me a broader overview and more access as a foreigner, in a more efficient way than trying to learn everything by rote.”

As Jeremy began using Ramesh’s system, he realised it was exactly what he needed. “The Gamaka Box Notation System solves that problem completely in a comprehensive and logical way,” he says.

Jeremy emphasises that the potential of the Gamaka Box Notation System extends beyond Indian classical music. “The kind of elaborate melodic motion that you see in Carnatic music and also in North Indian music, you can find in other musical traditions as well, including Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Chinese music, among others,” he explains.

He believes that these diverse musical traditions could also be effectively taught worldwide using this new notation system, opening up possibilities for broader musical understanding and education across different cultures.

For Jeremy, the Gamaka Box Notation System represents one of the most significant innovations in the music world in recent years. “I was trained as a composer in the Western classical system and have dealt with music notation my entire life. This is by far the most promising new notation system I’ve seen in my life. It really changed my whole way of thinking about sound and listening,” he reflects.

Soon after Ramesh and Jeremy met, Western classical musicians who were visiting Chennai from Germany performed a Carnatic raga on stage using the new notation system.

“Of course, we were very nervous and a little bit scared,” says Theodor Flindell, a classical violinist living and working in Berlin, about his performance in front of the knowledgeable Chennai crowd in 2016. “I mean, it was a big thing for us to go on stage, but the hall was filled and we got an immediate positive response… And it turned out to be a lovely experience actually, that I’ll never forget.”

Though he had to spend some time getting to know the notation system, Theodor agrees with Jeremy that it has opened new doors. He believes that one can truly understand a musician only if you play their compositions. “Any Western trained musician, at least theoretically, has the chance, you know, to get in touch with individuals in [Indian] music by actually playing the composition himself or herself, which is, of course, a totally different experience than just listening to it,” he says. “It’s just an unbelievable invention.”

Encouraged by such positive responses, Ramesh decided to transform Music Temple Academy—where he had been researching and promoting the Gamaka Box Notation System—into a music edtech company called Music Temple Private Ltd in 2020. And so, at the age of 57, Ramesh became a startup founder.

Music Temple aims to revolutionise music education—Carnatic, Hindustani, folk and film—by offering lessons through a software-as-a-service model. This approach is designed to make learning more accessible, flexible, and scalable for students across various musical traditions.

Ramesh met IIT Madras Director, Prof V Kamakoti, in 2022,and showcased the Gamaka Box Notation System to him. The meeting with Prof Kamakoti proved to be as fortuitous as his earlier encounter with Shriram Group’s Thyagarajan.

The sound of science

Prof Kamakoti, a violinist himself, is an ardent music lover and has spoken on many platforms about how music has helped him cope with stress.

“Any time that you are in any stress—or any semblance of sadness or happiness, you want to enjoy it with some humming of some music… And that keeps your complete mood aligned with that particular situation,” he says, speaking to YourStory from his fifth-floor office in the verdant IIT Madras campus in South Chennai.

“Music by itself has several unknown aspects—why certain feelings arise, why certain reactions happen when you listen to it—I strongly believe music is certainly a medicine for stress,” says Prof Kamakoti.

He is particularly fond of Carnatic music. “Carnatic music is life for me,” he adds.

This deep understanding and appreciation of music likely contributed to his immediate grasp of the significance of Ramesh’s new notation system and the role it could play in music education and beyond.

“So you see, music has a tremendous influence on many things, but there are several unknowns in that. And the way we can try to understand what is happening is by having a very comprehensive way of capturing these things. Capturing [the nuances of music] is what Ramesh is doing through his Gamaka Box.”

IIT Madras Director, Prof V Kamakoti, believes the Gamaka Box Notation System can play a vital role in preserving different banis (musical styles) of legendary musicians.

Prof Kamakoti pointed Ramesh towards IITM Pravartak Technologies Foundation and its CEO, Dr MJ Shankar Raman.

IITM Pravartak is a Section 8 company (a non-profit organisation) that hosts a Technology Innovation Hub at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Among its many initiatives, IITM Pravartak acts as an incubator for startups, offering support by taking a minor stake in them (a maximum of 8%), helping to nurture innovation and entrepreneurship. It currently supports about 40 startups.

Ramesh applied to become an incubatee at IITM Pravartak in 2022. During the vetting process when Ramesh presented to the team at IITM Pravartak, Dr Shankar Raman understood the significance of the new notation system within five minutes.

“When Ramesh told the idea the very first time we found out it has got huge applications, I mean probably even applications which they did not know,” says Dr Shankar Raman. “So the first five minutes when Ramesh told me I said, ‘Yes I think it should be done’ because he was only talking about teaching music… but I, being from a scientific frame of mind, thought a lot of things, not only teaching music.”

The mentorship of both IIT Madras and IITM Pravartak, which has a 5% stake in Music Temple, has been invaluable.

“They have given us immense strength and support,” says Srividhya, who is now a Director of Music Temple.

Music Temple received a patent for its Gamaka Box Notation System earlier this year and is currently in advanced negotiations to sign deals with several state governments to incorporate the system into their music education programmes. This marks a significant step forward in Ramesh’s vision to transform music education across the country.

Dr Shankar Raman believes that the new notation system could play a crucial role in preserving indigenous music that might otherwise fade away. He suggests it could be used to decipher patterns in the performances of musical geniuses, such as the late MS Subbulakshmi or the late Bhimsen Joshi, helping to uncover the secrets behind their brilliance. This, he says, could provide invaluable insights into the artistry and mastery of legendary performers, ensuring their musical legacy is both understood and preserved for future generations.

Prof Kamakoti agrees. “Preservation itself is a very important thing. So every bani [loosely translated as style] can be preserved. Like you have Madurai Mani Iyer bani, GN Balasubramaniam bani, and many other banis… Many [film] composers have their own bani, like Ilayaraja bani, Ramesh Vinayakam bani, AR Rahman bani… So each one would have approached a raga in a different way,” he says.

Western classical musician Jeremy is also convinced of the wide-ranging applications of the notation system. “I’m convinced that it has a lot of possibilities for technological innovation as well. I think it will also affect phonetics and linguistics. The way of thinking about sound that is encapsulated by the Gamaka Notation System is deeply profound.”

Uncharted market potential

Dr Shankar Raman baulks at any discussion about the market potential or the total addressable market for the Gamaka Box. “Usually, as a seed funding organisation and a deep tech organisation, I really don’t go by total addressable market,” he explains. “Even when we fund companies, we don’t go by total addressable market. In fact, when Music Temple came with some numbers, we just removed those numbers because we are interested in deep tech.”

He also questioned how one could assign a value to heritage. “For this product, I can’t talk about the addressable market, but I can tell you it has huge heritage value. And if you can put a value for heritage, then that is the addressable market.”

IITM Pravartak Technologies Foundation CEO Dr Shankar Raman believes the Gamaka Box Notation System is a simple idea with a huge heritage value. If Music Temple—the music edtech company behind the idea—is backed by a strong team that explores various applications, it has the potential to be a unicorn, he says.

One thing is certain: Ramesh’s new notation system will simplify the delivery of music lessons online. While various studies estimate the global online music learning market to range from several hundred million dollars to a few billion, they all project growth at a compound annual growth rate in the high teens for the next few years. And this is just one aspect of its potential.

Also, the younger generation of musicians have been more welcoming of the notation system.

Meenakshi S, 22, was doing her post-graduation in Carnatic music when she was introduced to the notation system. Though it took a while, she says it has helped her understand ragas faster and better.

“It definitely helped me because there are many misinterpretations when it comes to gamakas,” says Meenakshi, who is now doing an advanced diploma course at The Music Academy in Chennai. She has also enrolled as a student with Ramesh to learn music through the new notation system.

But wouldn’t a strict notation system limit the free expression of music—a quality that is essential for Indian classical ragas? Not necessarily, says Meenakshi.

“We have this thing called Kalpita Sangeetham and Kalpana Sangeetham. Kalpita Sangeetham is what we teach or what we learn. Kalpana Sangeetam is where we bring out our own creativity and imagination,” she says.

This is a little like learning to walk before attempting a marathon. The Gamaka Box Notation System will make the learning process faster. “This [the Gamaka Box] is Kalpita Sangeetham… When you learn, you have to learn what it is, and how it is given. Only later can you bring out your imagination.”

Rushab V, a Carnatic musician and guitarist, hasn’t yet experienced the Gamaka Box Notation System firsthand, but he believes that if it can accurately capture the nuances of gamakas, it would be a valuable tool.

“Of course, we’ve had notations to help, but this type of notation would make it much easier to understand gamakas in depth,” he says.

However, he’s unsure about its effectiveness without a teacher’s guidance. “I don’t know its viability as a standalone tool without a teacher… just learning from the notation,” says Rushab, who teaches music to about 10 children in his spare time.

The challenges ahead

Having a good product or service is just the beginning. History is filled with brilliant products that failed due to poor timing or an unprepared market. Examples like WebTV in 1996 or the Segway in 2001 show that even innovative ideas can struggle.

For Ramesh and his team at Music Temple, the challenge now is to get enough people using the Gamaka Box Notation System quickly to build critical mass. A key strategy will be assembling a strong team and focusing on the next generation of users.

“As a technology, it [the Gamaka Box Notation System] has succeeded already,” says IIT Madras’ Prof Kamakoti. “Commercially, it has to succeed. That’s what we are helping with.”

Dr Shankar Raman sees immense potential. “It’s a very simple idea. But simple ideas become great, not complex ones,” he explains. “Ramesh is a great musician, a genius… but I’m not sure if he’ll be as good a salesperson. Sales is a different art.” He stresses the importance of bringing the right talent on board to execute the vision. “If they have a strong team to explore various applications and go for it, they have the potential to be a unicorn.”

However, there’s also the challenge of getting people to embrace change, especially when it comes to tradition and music. As Shriram Group’s Thyagarajan points out, “People are moving away from anything that requires a bit of thinking and concentration for humanity.”

For now, Ramesh has two dreams: one is to see the London Symphony Orchestra perform Indian music using his system, and the other is to make Indian music accessible to anyone who wants to learn it, no matter how remote.

“Just like we studied Western classical music, they should study ours,” he says. “How can I not teach those who are eager to learn?”

(Feature image and infographic by Nihar Apte)

![Read more about the article [Year in Review 2021] Art as creation, communication, calture](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Art-Diversity-and-Appreciation-1640870422755-300x150.png)

![Read more about the article [Funding roundup] Bundle O Joy, Crypso, Windo, Zipteams, and others raise early stage round](https://blog.digitalsevaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/CF3-1655273097632-300x150.png)